Oral Health Care: Can access to services be improved?

Visit profiles to view data profiles and issue briefs from the series Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions as well as data profiles on young retirees and older workers.

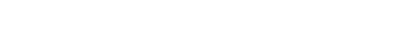

Over the past five decades the oral health of Americans has improved. Most oral disorders and diseases are less common today than they were 50 years ago. Tooth decay, however, remains the most common chronic disease among children ages 5 to 17.(1) Many oral disorders and diseases are preventable; yet, oral health has not been widely promoted. Furthermore, access to oral health care is limited, largely due to inadequate insurance coverage and a limited supply of providers. Substantial oral health disparities between populations of different income levels, ages, and cultures also exist. Increased attention to the prevention of oral disorders and diseases could improve the oral health of all Americans.

Oral health is associated with chronic conditions

A 2000 report released by the Surgeon General, Oral Health in America, alerted Americans about the importance of oral health to their overall health and well-being. Oral health has an impact on physical health, and is associated with chronic conditions including diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and cancer. Individuals with diabetes, for example, face a greater risk of developing oral diseases such as periodontal or gum disease. Oral health also affects one’s psychological development and health. Missing teeth can lead to diminished self-esteem.(2)

An individual’s ability to perform basic activities may also be affected by oral health.

- More than 51 million hours of school are lost each year by children due to dental-related illness.

- Employed adults lose more than 164 million hours of work each year due to oral health problems or dental visits.(3)

ORAL HEALTH IS MORE THAN JUST HEALTHY TEETH

Oral refers to the mouth which includes the teeth, gums, and supporting tissues. Diseases and disorders that can affect oral health include:

- Diseases such as tooth decay and periodontal or gum disease.

- Viral infections including cold and canker sores

- Birth defects such as cleft lip and palate and missing all or most teeth.

- RChronic oral-facial pain which can result from disorders of the jaw joints and chewing muscles, such as Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction or Craniomandibular Dysfuntion.

- Oral and throat cancers.

Community prevention efforts are effective, but not widespread

Oral diseases are largely preventable. Water fluoridation and dental sealants are two cost-effective strategies that have greatly reduced the occurrence of tooth decay across many communities. Both of these efforts have contributed to significant improvements in the oral health of the U.S. population since the early 1960s. Some populations, however, do not have access to these strategies and are particularly vulnerable to oral diseases.

FLUORIDATED WATER REDUCES TREATMENT COSTS

Community water fluoridation is largely responsible for the prevention of tooth decay. Children in communities with water fluoridation have 29 percent fewer cavities, compared to children in communities without it. Water fluoridation is also cost-effective – the per capita cost of water fluoridation over an individual’s lifetime is less than the cost of one dental filling. Savings are substantial – every dollar spent on community water fluoridation saves $7 to $42 in treatment costs, depending on the size of the community.(4) Yet, over 38 percent – 100 million people – of the U.S. population do not have access to water that contains enough fluoride to protect their teeth.(5) Populations in geographically isolated areas generally have limited access to optimally fluoridated water.

CHILDREN BENEFIT FROM DENTAL SEALANT PROGRAMS

The use of dental sealants – a plastic coating applied to the chewing surfaces of the back teeth – also reduces tooth decay, especially among children, yet less than 30 percent of children have received dental sealants.(6) School-based dental sealants programs provide preventive services to children who otherwise may not have access to dental care, such as children from low-income households. Children receiving sealants at school have 60 percent fewer tooth decays for up to 2 to 5 years afterwards. Still, only 3 percent of poor children receive dental sealants.(7)

DENTAL SEALANT PROGRAMS IN TWO STATES IMPROVE THE ORAL HEALTH OF CHILDREN

More than half of the states – 29 – provide preventive services to 193,000 children through dental sealant programs. Several states, including Ohio and Wisconsin, have devoted a substantial amount of resources to school and community-based efforts that target children at high-risk for dental decay and least likely to receive care. In Ohio, over one-third of the counties have school-based dental sealant programs. Over the past ten years, the proportion of 8 year olds receiving dental sealants has almost tripled, from 11 percent to 30 percent. Wisconsin has also had great success with its statewide effort to improve the oral health of low-income children through school and community partnerships. During the 2000-2001 school year, 40 new community-based sealant programs were established across the state. As a result, more than 4,500 children across 40 counties received dental selants that year.(8)

Vulnerable populations experience more oral diseases and receive less care

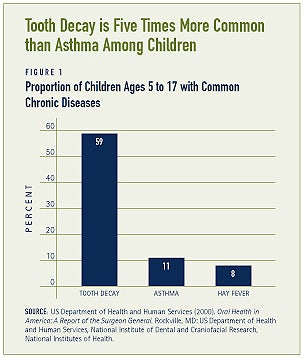

A large proportion of the population does not receive any dental care (see Figure 2). Some populations, including low-income individuals and racial and ethnic minorities, are less likely to receive dental services.

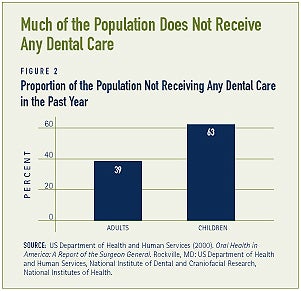

Compared to the higher-income population, the low-income population experiences more oral diseases and is less likely to receive care (see Figure 3). Poor children experience twice the amount of tooth decay as do non-poor children.(9) Similarly, over one-third of poor adults suffer from tooth decay, compared to 11 percent of non-poor adults.(10)

Oral health conditions and diseases increase with age. Oral and pharyngeal cancers are diagnosed primarily among people age 65 and older. Gum disease and loss of teeth are also more common among older adults. Compared to younger adults, older adults are less likely to visit a dentist. Obtaining adequate oral health care is particularly problematic for older Americans who reside in a long-term care facility.(11)

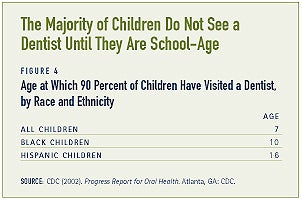

Racial and ethnic minority populations are also more likely to experience poor oral health. For example, Hispanic children have higher rates of tooth decay than non-Hispanic white children.(12) The majority of Hispanic children do not see a dentist until age 16 (see Figure 4). American Indians also experience high rates of oral diseases. About one-third of American Indian adolescents have untreated tooth decay – a proportion that is three times that of non-Indian adolescents. Only about 1 in 4 Americans Indians has access to dental services.(13)

Insurance coverage for oral health care is inadequate

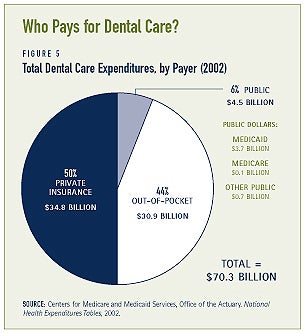

In 2002, annual expenditures for dental services in the U.S. were $70.3 billion or 5 percent of total health care expenditures. Private sources, including private insurance and out-of-pocket spending by consumers, finance an overwhelming majority – 94 percent – of dental care. Only 6 percent of dental care is financed by public payers, primarily through the federal-state Medicaid programs (see Figure 5). In addition to the Medicaid program, federal agencies such as the Indian Health Service and the Health Resources and Services Administration, provide some care to underserved populations. Still, many Americans do not have adequate insurance coverage. Over 108 million children and adults lack dental insurance – over 2.5 times the number without medical insurance.(14)

DENTAL INSURANCE IS LARGELY TIED TO EMPLOYEMENT

Private dental insurance is primarily employment-based. Private dental care benefits are available to more than half – 59 percent – of full-time employees in medium and large businesses. In comparison, smaller businesses are less likely to offer dental coverage.(15) And, most employers of low-wage workers do not offer a dental insurance benefit.(16) In 1998, some 22.6 million employees were receiving employer-provided dental benefits.(17) Many older adults lose their private dental insurance when they retire – less than 20 percent of Americans age 75 and older have any form of private dental insurance.(18) As a result, many older adults must either pay out-of-pocket or forgo dental care or treatment. The Medicaid program – a program that is jointly financed by the federal and state governments and administered by the states – may be an option for some individuals with low incomes or disabilities who do not have access to employer-provided private insurance or cannot afford to pay the premiums.

SERVICES PROVIDED BY PUBLIC PROGRAMS ARE RATHER LIMITED

Private dental insurance generally covers preventive care, including dental exams and sealants, and restorative procedures. Restorative procedures are usually limited to fillings, however. Periodontal care and oral surgery may also be covered by private insurance. Orthodontic care is covered less often, and cosmetic procedures are typically not covered. In comparison, coverage provided by state Medicaid programs is more limited. States are required to provide Medicaid-eligible children (under age 21) with comprehensive preventive, restorative, and emergency dental services. States may also provide services to low-income children through their State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). State Medicaid programs are not required to provide dental care to adults, however. Only 10 states provide full or comprehensive dental benefits to adults, and six states do not offer any adult dental benefits. Emergency services, such as tooth extractions and oral surgery, are provided to adults in 20 states.(19) Less than one-fifth of Medicaid beneficiaries receive dental care.(20)

THE ABCD PROGRAM INCREASES USE AMONG MEDICAID BENEFICIARIES

The Access to Baby and Child Dentistry (ABCD) program in Washington is designed to increase access to preventive and rehabilitative care for low-income children under age 6. The ABCD program is a unique partnership between the state Medicaid program, the Spokane Dental Society, the Spokane Health District, and the University of Washington. After attending a dental education program, families of the children are matched with a participating dentist who has been trained to provide care to yound children. In addition to being educated about the importance of maintaining good oral health, families are taught how to practice good oral hygiene, how to make and keep appointments, and how to help their children behave properly in a dental office.

The ABCD program has been successful at increasing service use and provider participation. Among children under age 2, for example, some 12 percent of those enrolled in the program received dental serices, compared to 6 percent of children not enrolled in the program in 2001. Over 350 dentists have been trained to provide services to children.(21) The potential for long-term cost savings is also great. The per child cost of preventing a tooth decay is substantially less than the costs associated with treating a tooth decay.(22)

RECEIPT OF SERVICES IS LARGELY DEPENDENT ON TYPE OF COVERAGE

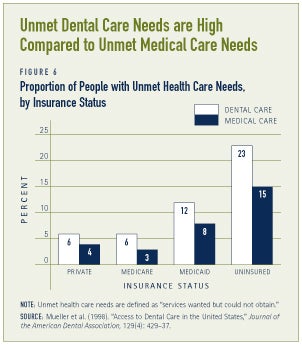

Individuals with private insurance are more likely to receive dental care. Some 70 percent of those with private insurance saw a dentist in the past year, compared to 51 percent of those without any dental insurance. The disparity between the privately insured and uninsured populations is even larger for children and older adults. Unmet dental care needs are also associated with type of insurance coverage. Almost one-tenth of the population wants, but does not obtain, dental care. Unmet dental care needs are highest among individuals without insurance (see Figure 6).

The limited supply of dental providers is problematic

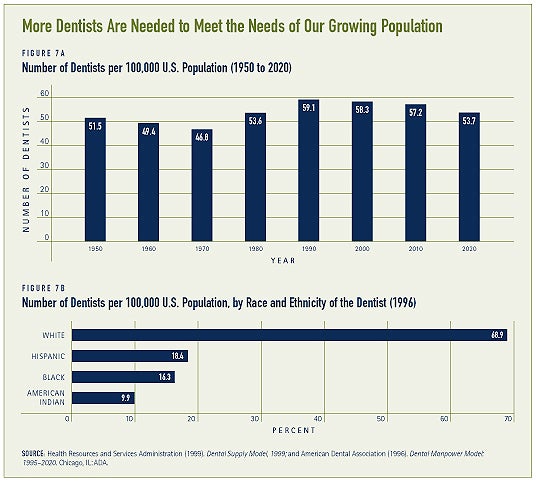

The lack of dental providers is a major barrier to obtaining dental care. There has been a significant decline in the number of practicing dentists over the past twenty years, and a projected decline in dental school graduates (see Figure 7a). Between 1986 and 1993, six dental schools closed, followed by one more in 2001. During this time, only one new school has opened. Dental schools have also experienced reductions in class sizes – the percent of graduating dentists declined by 40 percent between 1986 and 2000.(23) In addition to a general shortage of dentists, there is a shortage of dentists specializing in pediatric or geriatric care.

The lack of providers is even more pronounced in underserved areas. In 1998, there were 1,036 dental Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA’s) requiring about 1 dentist per 4,000 persons. By 2002, the number of HPSA’s had almost doubled to 1,953. The majority – 90 percent – of dentists practice in the private sector. Safety-net facilities – health care centers that serve uninsured individuals or individuals who do not have the money to pay for care – are often located in isolated, rural areas and poor, urban areas. Safety-net facilities, including community-based clinics, migrant and rural health centers, school-based programs, and mobile van programs, are few in number and many do not provide dental care. Only 56 percent of federally-funded community and migrant health centers provide dental care.(24)

RACIAL AND ETHNIC MINORITIES ARE UNDER-REPRESENTED IN THE DENTAL PROFESSION

Compared to the general population, racial and ethnic minorities are under-represented in the dental profession (see Figure 7b). Minority dentists are more likely to practice in minority communities. African-American and Hispanic-American dentists disproportionately serve African-Americans and Hispanic Americans, respectively, in their private practices.(25) Furthermore, patients are more likely to seek health care from professionals of a similar culture or background. Substantial increases in the proportions of ethnic and racial minorities in the population heighten the need for a more diverse dental workforce. Additionally, dentists and their staff are more likely to need special skills, sensitivity, and competency to deal with complex cultural and social issues.

INCENTIVES COULD INCREASE THE SUPPLY OF DENTAL PROVIDERS

Strategies to increase the supply of dental providers have not been widely implemented. Additional resources could, however, increase the number of dental providers available today and in the future. Although the establishment of new dental schools is an important first step, enrollment also needs to be increased. Barriers that discourage students – generally, as well as from low-income, minority, and rural populations – from choosing a dental career must be removed. This can be done by providing incentives such as scholarship, tuition reimbursement, and loan repayment or forgiveness programs. The Indian Health Service (IHS) operates a loan repayment program – where health professionals agree to practice full-time at an IHS facility or tribal site in exchange for repayment of their educational loan. However, funding for this program has remained relatively stable for the past eight years, while student debt has nearly doubled during this time.(26)

Recently, additional resources were provided by the federal government to help address the dental shortage in underserved areas. The Health Care Safety Net Amendments Act of 2002 authorized $50 million for grants, over a five-year period beginning in Fiscal Year 2002, to states to develop and implement programs, including loan forgiveness and loan repayment assistance, that address the dental workforce needs of dental HPSAs.(27)

SEVERAL STATES HAVE CHANGED LAWS TO INCREASE ACCESS TO PREVENTIVE CARE

Most state laws restrict the provision of preventive oral health services to dentists. Dental hygienists are allowed to provide a defined scope of preventive services, though state laws require them to be supervised by a adentist. Several states have expanded the duties of dental hygienists and assistants. Colorado, for example, allows dental hygienists to provide oral health services without the supervision of a dentist. Washington also allows hygienists to practice independently under certain conditions.

The reimbursement procedure has not been changed, however. Dental hygienists do not have their own provider number for direct billing, and therefore must maintain ties to a dentist. Because the enactment of changes to state laws may be a slow and difficult process, some states maximize resources that are currently available. For example, a program in North Carolina trains medical providers to apply fluoride varnish to children between the ages of nine months and three years. The program has reduced cavities by up to 30 percent.(28)

INCREASING REIMBURSEMENT RATES TO DENTAL PROVIDERS CAN ALSO HELP

Medicaid reimbursement rates for oral health services are low compared to fees in the private sector. Low dental reimbursement rates, which vary by state, are a major deterrent to provider participation in Medicaid. According to a 1998 survey by the American Dental Association, the number of dentists enrolled as providers in Medicaid ranged from 1 in Delaware to 3,788 in New Jersey.(29)

Several states, including Michigan and New Mexico, have increased the number of Medicaid providers by raising reimbursement rates. The “Healthy Kids Dental” program in Michigan has increased both the number of dental visits by low-income children and the number of Medicaid providers.(30) The proportion of eligible children seeing a dentist has increased from 18 percent to 44 percent, and the number of providers participating in the program has increased by more than 300 percent.

Use of dental services by some populations may be low

Being insured or having access to a dental provider does not ensure service use. Some individuals might not know when and how to obtain dental services. Outreach activities and efforts that coordinate oral health care with other health care services could increase service use. Language barriers may also prevent individuals from accessing dental care. For example, non-English speaking beneficiaries in the California dental Medicaid program (Denti-Cal) report substantial difficulty communicating with their dental providers.(31) The Dental Health Program in North Carolina, which helps low-income children access dental care, addresses the needs of non-English speaking patients through a variety of efforts. Staff at each dental care center participates in cultural sensitivity classes, and there is a bilingual staff member at each center to help ensure that the Hispanic population receives accurate information. In addition, patients are provided with translated documents, and a telephone interpretation service is available to help non-English speaking patients make appointments.(32)

Conclusion

In recent years oral health has been gaining more attention. Although efforts to increase access to services are increasingly more common, there is still much work that could be done – at the individual, professional, and community level – to improve the oral health status of our population.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

2. R. Warren (1999). Oral Health for All: Policy for Available, Accessible, and Acceptable Care. Washington, DC: Center for Policy Alternatives.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services (2003). A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH Publication No. 03-5303).

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002). “Preventing Dental Caries,” Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services (2003).

10. CDC (2001). “Oral Health for Adults,” Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

13. Indian Health Service (2002). An Oral Health Survey of American Indian and Alaska Native Dental Patients: Findings, Regional Differences and National Comparisons. Rockville, MD: IHS.

16. S. Beetstra et al. (2002). “A ‘Health Commons’ Approach to Oral Health for Low-Income Populations in a Rural State,” American Journal of Public Health, 92(1):pp-pp.

18. Oral Health America (2003). A State of Decay: The Oral Health of Older Americans. Chicago, IL: OHA.

20. Center for Policy Alternatives (1999). “Dental Coverage Under Medicaid,” Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: CPA.

21. The ABCD Program (http://www.abcd-dental.org/)

22. P. Milgrom et al. (unpublished paper). The Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of the Access to Baby and Child (ABCD) Dentistry Program in Washington State.

23. Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (2003). “Access to Oral Health Services: Workforce Development,” Best Practice Approach Report. Jefferson City, MO: ASTDD.

27. National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc. Fact Sheet on Public Law 107-251 (S.1533). Washington, DC: NACHC.

28. FirstHealth of the Carolinas (2003). Dental Book. Available at: http://www.communityvoices.org.

30. ADA (2003). State Innovations to Improve Dental Access for Low-Income Children: A Compendium. Chicago, IL: ADA.

31. Health Consumer Alliance and Health Rights Hotline (2002). Denti-Cal Denied: Consumers’ Experiences Accessing Dental Services in California’s Medi-Cal Program.

32. FirstHealth of the Carolinas (2003).

ABOUT THE ISSUE BRIEFS

This is the sixth in a series of Issue Briefs on Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions. This series is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Lee Thompson wrote this Issue Brief.

The Center on an Aging Society is a non-partisan policy group located at the Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the financial and health security of families and people of all ages.