Cultural Competence in Health Care: Is it important for people with chronic conditions?

Visit profiles to view data profiles and issue briefs from the series Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions as well as data profiles on young retirees and older workers.

The increasing diversity of the nation brings opportunities and challenges for health care providers, health care systems, and policy makers to create and deliver culturally competent services. Cultural competence is defined as the ability of providers and organizations to effectively deliver health care services that meet the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients.(1) A culturally competent health care system can help improve health outcomes and quality of care, and can contribute to the elimination of racial and ethnic health disparities. Examples of strategies to move the health care system towards these goals include providing relevant training on cultural competence and cross-cultural issues to health professionals and creating policies that reduce administrative and linguistic barriers to patient care.

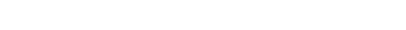

Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately burdened by chronic illness

Racial and ethnic minorities have higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases. The consequences can range from greater financial burden to higher activity limitations.

Among older adults, a higher proportion of African Americans and Latinos, compared to Whites, report that they have at least one of seven chronic conditions — asthma, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, or anxiety/ depression.(2) These rank among the most costly medical conditions in America.(3)

African Americans and American Indians/Alaska Natives are more likely to be limited in an activity (e.g., work, walking, bathing, or dressing) due to chronic conditions.(4)

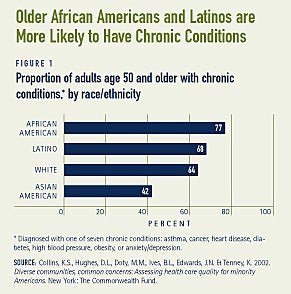

The population at risk for chronic conditions will become more diverse

Although chronic illnesses or disabili- ties may occur at any age, the likelihood that a person will experience any activity limitation due to a chronic condition increases with age.(5) In 2000, 35 million people — more than 12 percent of the total population — were 65 years or older.(6) By 2050, it is expected that one in five Americans — 20 percent — will be elderly. The population will also become increasingly diverse (see Figure 2). By 2050, racial and ethnic minorities will comprise 35 percent of the over 65 pop-ulation.(7) As the population at risk of chronic conditions becomes increasingly diverse, more attention to linguistic and cultural barriers to care will be necessary.

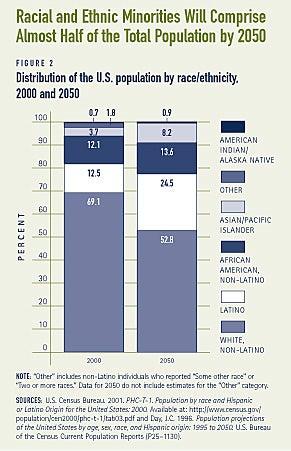

Access to health care differs by race and ethnicity

Having a regular doctor or a usual source of care facilitates the process of obtaining health care when it is needed. People who do not have a regular doctor or health care provider are less likely to obtain preventive services, or diagnosis, treatment, and management of chronic conditions. Health insurance coverage is also an important determinant of access to health care. Higher proportions of minorities compared to Whites do not have a usual source of care and do not have health insurance (see Figures 3A and 3B).

Language and communication barriers are problematic

Of the more than 37 million adults in the U.S. who speak a language other than English, some 18 million people — 48 percent — report that they speak English less than “very well.”(8) Language and communication barriers can affect the amount and quality of health care received. For example, Spanish-speaking Latinos are less likely than Whites to visit a physician or mental health provider, or receive preventive care, such as a mammography exam or influenza vaccination.(9) Health service use may also be affected by the availability of interpreters. Among non-English speakers who needed an interpreter during a health care visit, less than half — 48 percent — report that they always or usually had one.(10)

Language and communication problems may also lead to patient dissatisfaction, poor comprehension and adherence, and lower quality of care. Spanish-speaking Latinos are less satisfied with the care they receive and more likely to report overall problems with health care than are English speakers.(11) The type of interpretation service provided to patients is an important factor in the level of satisfaction. In a study comparing various methods of interpretation, patients who use professional interpreters are equally as satisfied with the overall health care visit as patients who use bilingual providers. Patients who use family interpreters or non-professional interpreters, such as nurses, clerks, and technicians are less satisfied with their visit.(12)

Low literacy also affects access to health care

The 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey found that 40 to 44 million Americans do not have the necessary literacy skills for daily functioning.(13) The elderly typically have lower levels of literacy, and have had less access to formal education than younger populations.(14) Older patients with chronic diseases may need to make multiple and complex decisions about the management of their conditions. Racial and ethnic minorities are also more likely to have lower levels of literacy, often due to cultural and language barriers and differing educational opportunities.(15) Low literacy may affect patients’ ability to read and understand instructions on prescription or medicine bottles, health educational materials, and insurance forms, for example. Those with low literacy skills use more health services, and the resulting costs are estimated to be $32 to $58 billion — 3 to 6 percent — in additional health care expenditures.(16)

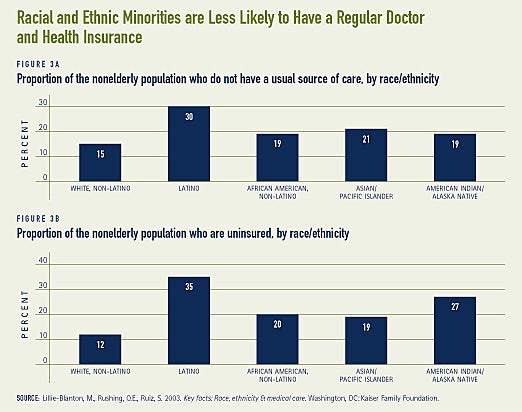

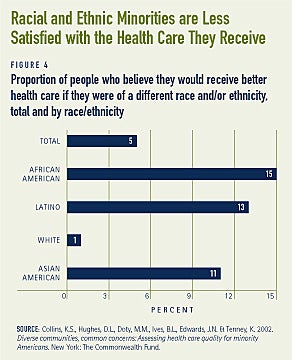

Lack of cultural competence may lead to patient dissatisfaction

People with chronic conditions require more health services, therefore increasing their interaction with the health care system. If the providers, organizations, and systems are not working together to provide culturally competent care, patients are at higher risk of having negative health consequences, receiving poor quality care, or being dissatisfied with their care. African Americans and other ethnic minorities report less partnership with physicians, less participation in medical decisions, and lower levels of satisfaction with care.(17) The quality of patient-physician interactions is lower among non-White patients, particularly Latinos and Asian Americans. Lower quality patient-physician interactions are associated with lower overall satisfaction with health care.(18)

African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, are more likely than Whites to report that they believe they would have received better care if they had been of a different race or ethnicity (see Figure 4). African Americans are more likely than other minority groups to feel that they were treated disrespectfully during a health care visit (e.g., they were spoken to rudely, talked down to, or ignored). Compared to other minority groups, Asian Americans are least likely to feel that their doctor understood their background and values and are most likely to report that their doctor looked down on them.(19)

WHAT IS CULTURAL COMPETENCE IN HEALTH CARE?

Individual values, beliefs, and behaviors about health and well-being are shaped by various factors such as race, ethnicity, nationality, language, gender, socioeconomic status, physical and mental ability, sexual orientation, and occupation. Cultural competence in health care is broadly defined as the ability of providers and organizations to understand and integrate these factors into the delivery and structure of the health care system. The goal of culturally competent health care services is to provide the highest quality of care to every patient, regardless of race, ethnicity, cultural background, English proficiency or literacy. Some common strategies for improving the patient-provider interaction and institutionalizing changes in the health care system include:(20)

1. Provide interpreter services

2. Recruit and retain minority staff

3. Provide training to increase cultural awareness, knowledge, and skills

4. Coordinate with traditional healers

5. Use community health workers

6. Incorporate culture-specific attitudes and values into health promotion tools

7. Include family and community members in health care decision making

8. Locate clinics in geographic areas that are easily accessible for certain populations

9. Expand hours of operation

10. Provide linguistic competency that extends beyond the clinical encounter to the appointment desk, advice lines, medical billing, and other written materials

Cultural competence is an ongoing learning process

In order to increase the cultural competence of the health care delivery system, health professionals must be taught how to provide services in a culturally com-petent manner. Although many different types of training courses have been developed across the country, these efforts have not been standardized or incorpo-rated into training for health profession-als in any consistent manner.(21) Training courses vary greatly in content and teaching method, and may range from three-hour seminars to semester-long academic courses. Important to note, however, is that cultural competence is a process rather than an ultimate goal, and is often developed in stages by building upon previous knowledge and experience.

TRAINING APPROACHES THAT TEACH FACTS ABOUT SPECIFIC GROUPS ARE BEST COMBINED WITH CROSS-CULTURAL SKILL-BASED APPROACHES THAT CAN BE UNIVERSALLY APPLIED

Approaches that focus on increasing knowledge about various groups, typically through a list of common health beliefs, behaviors, and key “dos” and “don’ts,” provide a starting point for health pro-fessionals to learn more about the health practices of a particular group. This approach may lead to stereotyping and may ignore variation within a group, however. For example, the assumption that all Latino patients share similar health beliefs and behaviors ignores im-portant differences between and within groups. Latinos could include first-generation immigrants from Guatemala and sixth-generation Mexican Americans in Texas. Even among Mexican Americans, differences such as generation, level of acculturation, citizenship or refugee status, circumstances of immigration, and the proportion of his or her life spent in the U.S. are important to recognize.

It is almost impossible to know everything about every culture. Therefore, training approaches that focus only on facts are limited, and are best combined with approaches that provide skills that are more universal. For example, skills such as communication and medical history-taking techniques can be applied to a wide diversity of clientele. Curiosity, empathy, respect, and humility are some basic attitudes that have the potential to help the clinical relationship and to yield useful information about the patient’s individual beliefs and preferences. An approach that focuses on inquiry, reflection, and analysis throughout the care process is most useful for acknowledging that culture is just one of many factors that influence an individual’s health beliefs and practices.(22)

GUIDELINES FROM PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS HELP PROMOTE CULTURAL COMPETENCE

Many professional organizations representing a variety of health professionals, such as physicians, psychologists, social workers, family medicine doctors, and pediatricians have played an active role in promoting culturally competent practices through policies, research, and training efforts. For example, the American Medical Association provides information and resources on policies, publications, curriculum and training materials, and relevant activities of physician associations, medical specialty groups, and state medical societies.(23)

Several organizations have instituted cultural competence guidelines for their memberships. For example, based on ten years of work, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine has developed guidelines for curriculum material to teach cultural sensitivity and competence to family medicine residents and other health professionals. These guidelines focus on enhancing attitudes in the following areas:(24)

- Awareness of the influences that sociocultural factors have on patients, clinicians, and the clinical relationship.

- Acceptance of the physician’s respon-sibility to understand the cultural aspects of health and illness

- Willingness to make clinical settings more accessible to patients

- Recognition of personal biases against people of different cultures

- Respect and tolerance for cultural differences

- Acceptance of the responsibility to combat racism, classism, ageism, sexism, homophobia, and other kinds of biases and discrimination that occur in health care settings.

ACCREDITATION STANDARDS THAT ADDRESS CULTURAL COMPETENCE IN MEDICAL SCHOOLS HAVE THE POTENTIAL TO REACH MANY FUTURE PHYSICIANS

Accreditation standards are important tools that can have widespread effects on the cultural competence of medical students, health care professionals, and health care organizations. For example, the Liaison Committee on Medical Edu-cation (LCME) — the nationally recognized accreditation body for medical schools in the U.S. and Canada — recently mandated higher standards for curriculum material on cultural competence than were previously in place. As a result, medical schools must now provide students with the skills to understand how people of diverse cultures and belief systems perceive health and illness and respond to various symptoms, diseases, and treatments. Students must also be able to recognize and appropriately address racial and gender biases in themselves, in others, and in the delivery of health care.(25)

Commitment to cultural competence is growing among health care providers and systems

Health systems are beginning to adopt comprehensive strategies to respond to the needs of racial and ethnic minorities for numerous reasons. First, there are increasingly more state and federal guidelines that encourage or mandate greater responsiveness of health systems to the growing population diversity. Second, these strategies may be seen as essential to meeting the federal government’s Healthy People 2010 goal of eliminating racial and ethnic health disparities. Third, many health systems are finding that developing and implementing cultural competence strategies are a good business practice to increase the interest and participation of both providers and patients in their health plans among racial and ethnic minority populations.

In addition to increasing the cultural competence of health care providers, organizational accommodations and policies that reduce administrative and linguistic barriers to health care are also important. Policies that strive to achieve cultural competence throughout the organization must address issues on all levels, from the organization’s top management to clinicians to office staff to billing and administrative staff. Organizational policies that address language and literacy barriers have been among the most successful efforts.

BILINGUAL AND BICULTURAL SERVICES ARE EFFECTIVE

Traditionally, community health centers that serve the Asian American or Latino communities have the most fully developed linguistic capabilities. For example, Asian Counseling and Referral Services (ACRS) in Seattle is a community-based mental health organization that effectively addresses language needs. They try to provide bilingual and bicultural clinicians that match the client’s background. When this is not possible, ACRS provides trained staff to act as co-providers with a licensed mental health professional. These trained individuals act not only as interpreters, but also help provide a cultural context for the client’s beliefs and practices. Stemming from 30 years of experience in this arena, ACRS has developed a training curriculum, “Building Bridges: Mental Health Interpreter Training for Interpreters of Southeast Asian Languages.” This curriculum will be used as a model for a national mental health interpreter training project to address the needs of limited-English speaking people. This national project includes training for interpreters, trainers, and health providers, as well as a mental health interpreter certification process.(26)

Within the Latino community, the use of promotoras, also known as peer edu-cators, is becoming increasingly popular. Promotoras are generally ordinary people from hard-to-reach populations who act as bridges between their community and the complicated world of health care. They learn about health care principles from doctors or non-profit groups, and share their knowledge with their com-munities. The peer education model is not only cost-effective, but also has been shown to be more effective in terms of reaching populations who find the information more credible coming from someone with a familiar background.(27)

ASSESSING LITERACY LEVELS CAN BREAK DOWN BARRIERS

Methods employed to assess literacy levels include the use of screening instruments that test for certain skills related to functional literacy or less formal tools that allow health care professionals to determine a person’s comfort level with various modes of communication. For example, at the To Help Everyone (T.H.E.) Clinic in Los Angeles, nurses and health care professionals speak individually with patients when they arrive at the health clinic to determine whether the patient prefers to learn by using written materials, pictures, verbal counseling, or some other technique. This method of assessment allows the patient to identify their own learning style preference without having to take a literacy test; it also reduces feelings of fear or humiliation that may occur when singled out.(28)

FEDERAL STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES FOR PROVIDING CULTURALLY AND LINGUISTICALLY APPROPRIATE CARE

1. The Department of Health and Human Services has provided important guidance on how to ensure culturally and linguistically appropriate health care services. The Office for Civil Rights published “Title VI Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination as it Affects Persons with Limited English Proficiency.” Very few states have developed standards for linguistic access. States that have developed such standards have focused on managed care organizations, contracting agreements with providers, and specific health and mental health services in defined settings.(29)

2. In August 2000, the Health Care Financing Administration (now Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) issued guidance to all state Medicaid directors regarding interpreter and translation services, emphasizing that federal matching funds are available for states to provide oral interpretation and written translation services for Medicaid beneficiaries.(30)

3. In December 2000, the Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services issued 14 national standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in health care. These standards are intended to correct current inequities in the health services system and to make these services more responsive to the individual needs of all patients. They are designed to be inclusive of all cultures, with a particular focus on the needs of racial, ethnic, and linguistic population groups that experience unequal access to the health care system. The CLAS standards provide consistent definitions of culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care and offer a framework for the organization and implementation of services. CLAS standards can be found at http://www.omhrc.gov/CLAS/

4. In 2002, two guides were developed to assist managed care plans with cultural and linguisti-cally appropriate services: “Providing Oral Linguistic Services: A Guide for Managed Care Plans” and “Planning Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services: A Guide for Managed Care Plans.” Both guides can be found at www.cms.gov/healthplans/quality/project03.asp

Conclusion

Cultural competence is not an isolated aspect of medical care, but an important component of overall excellence in health care delivery. Issues of health care quality and satisfaction are of particular concern for people with chronic conditions who frequently come into contact with the health care system. Efforts to improve cultural competence among health care professionals and organizations would contribute to improving the quality of health care for all consumers.

1. Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., & Carrillo, J. E. 2002. Cultural competence in health care: Emerging frameworks and practical approaches. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

2. Collins, K.S., Hughes, D. L., Doty, M. M., Ives, B. L. Edwards, J. N., & Tenney, K. 2002. Diverse communities, common concerns: Assessing health care quality for minority Americans. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

3. Druss, B.G., Marcus, S.C., Olfson, M., Pincus, H.A. 2002. The most expensive medical conditions in America. Health Affairs, 21, 105-111.

4. Fried, V. M., Prager, K., MacKay, A. P., Xia, H. 2003. Health, United States, 2003: Chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

6. U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2000. Table DP-1, Profile of general demographic characteristics: 2000. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved November 13, 2003, from http://factfinder.census.gov.

7. Day, J. C. 1996. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. (U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P25-1130). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

8. Center on an Aging Society analysis of data from the 2000 Census, QT-P17, Ability to speak English. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census Summary File 3 ? Sample Data.

9. Fiscella, K., Franks, P., Doescher, M. P., & Saver, B. G. 2002. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity and language among the insured: Findings from a national sample. Medical Care, 40(1), 52-59.

11. Carrasquillo, O., Orav, E. J., Brennan, T. A., Burstin, H. R. 1999. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 82-87.

12. Lee, L. J, Batal, H. A., Maselli, J. H. Kutner, J. S. 2002. Effect of Spanish interpretation method on patient satisfaction in an urban walk-in clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17, 641-646.

13. Kirsch, I. S., Jungeblut, A., Jenkins, L., & Kolstad, A. 2002. Adult literacy in America: A first look at the results of the National Adult Literacy Survey, Third Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Office of Educational Research and Improvement. Retrieved November 13, 2003, from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93275.pdf.

14. Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L. 2003. Patient-provider communication: The effect of race and ethnicity on process and outcomes of healthcare. In B. D. Smedley, A. Y. Stith & A. R. Nelson (Eds.) Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (pp. 552-593). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

15. Wilson, J.F. 2003. The crucial link between literacy and health. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139, 875-878.

16. Center for Health Care Strategies. 2003. Impact of low health literacy skills on annual health care expenditures. Lawrenceville, NJ: Author. Retrieved November 17, 2003, from http://www.chcs.org/ resource/pdf/h13.pdf.

18. Saha, S., Arbelaez, J. J., Cooper, L. A. 2003. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1713-1719.

20. Brach, C. & Fraser, I. 2000. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review, 57 (Supplement 1), 181-217.

21. American Institutes for Research. 2002. Teaching cultural competence in health care: A review of current concepts, policies, and practices. Report prepared for the Office of Minority Health. Washington, DC: Author.

22. Bonder, B., Martin, L., Miracle, A. 2001. Achieving cultural competence: The challenge for clients and healthcare workers in a multicultural society. Generations, 25, 35-42.

23. American Medical Association. 1999. Cultural Competence Compendium. Chicago: Author.

24. American Institutes for Research. 2002.

25. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 2001. Functions and structure of a medical school. Retrieved February 2, 2004, from http:// www.lcme.org/functions2003september.pdf.

26. Asian Counseling and Referral Service. 2003. ACRS participates in national effort to train mental health interpreters. Seattle, WA: Author. Retrieved November 25, 2003, from http://www.acrs.org/eventsNews/ newsletter.htm

27. Kolker, C. 2004, January 5. “Familiar faces bring health care to Latinos.” The Washington Post, p. A03.

28. Kiefer, K. M. 2001. Health literacy: Responding to the need for help. Washington, DC: Center for Medicare Education.

29. Goode, T., Sockalingam, S., Brown, M., & Jones, W. 2001. Linguistic competence in primary health care delivery systems: Implications for policy makers. Washington, DC: National Center for Cultural Competence, Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy, Georgetown University Child Development Center.

30. Westmoreland, T. M. 2000, August 31. Letter to State Medicaid Directors from Timothy M. Westmoreland, Director, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved November 18, 2003, from http:// cms.hhs.gov/states/letters/smd83100.asp.

ABOUT THE ISSUE BRIEFS

This is the fifth in a series of Issue Briefs on Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions. This series is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Issue Briefs accompany the Center’s ongoing series of Data Profiles in the same series. Emily Ihara wrote this Issue Brief.

The Center on an Aging Society is a non-partisan policy group located at Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the financial and health security of families and people of all ages.