Adult Children

Number 2, May 2005

Visit profiles to view data profiles on chronic and disabling conditions and on young retirees and older workers.

The Likelihood of Providing Care for an Older Parent

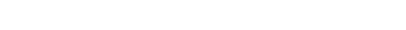

Most long-term care provided to older persons living in the community is provided by family and friends. Among family caregivers, adult children are most likely to assume the role of primary caregiver. In 1999, adult children accounted for 44 percent of primary family caregivers, the largest proportion of primary caregivers to people age 65 or older living in the community with limitations performing basic everyday activities (see Figure 1).(1)

This Profile provides an overview of adult children who are primary caregivers to an older parent that needs assistance performing one or more basic everyday activities. Basic everyday activities are Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs), such as doing housework, managing finances, medication or transportation; and/or Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) such as eating, bathing, using the toilet, or moving about. Futhermore, this Profile examines adult children that have living parents but are not primary caregivers as well as adults without any living parents. Adult children, non-caregivers and adults without living parents could be caregivers in another capacity, such as a secondary caregiver or a caregiver to a spouse or sibling. Throughout this Profile, the term “parent” is used to encompass both parents and parents-in-law, the term “older people” refers to people age 65 or older, and “adult” encompasses only those age 51 or older. “Primary caregivers” are uncompensated and provide the majority of the care received.

Over 7 million adult children are primary caregivers to their parent(s)

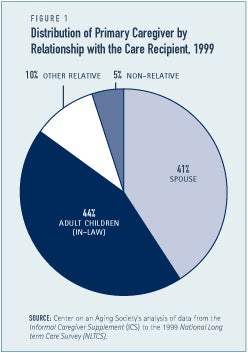

Among adults age 51 or older more than one in ten are providing assistance with basic everyday activities to their parent(s) (See Figure 2). It is anticipated that a larger proportion of adult children are likely to become caregivers as the population age 65 or older continues to grow at a faster rate than the population under age 65. The population age 65 or older is expected to increase 101 percent between 2000 and 2030 at a rate of 2.3 percent annually.(2) The population most likely to provide care, spouses and adult children ages 45 to 64, is expected to increase only 25 percent between 2000 and 2030 at a rate of 0.8 percent annually.(3) The disparity between potential care recipients and potential caregivers could add pressure on adult children to devote time and resources to assist their parents with basic everyday activities.

Adult children devote time and resources to caregiving

The amount of time spent providing direct care can vary dramatically, ranging from a few hours to more than 40 hours per week. On average, adult children provide 421 hours of care annually.(4) About 267 hours are spent assisting parents with limitations in IADLs and 169 hours are spent assisting parents with limitations in ADLs.

Adult children provide financial assistance to their parents

Long-term care is not just limited to physical assistance. Caregivers are more likely to provide financial assistance to their parents than adult children who are not caregivers. Almost 13 percent of caregivers provide financial assistance compared to 6 percent of other adult children. This results in an average transfer of $2,661 annually to parents receiving physical assistance from their adult children caregivers compared to $2,530 from adult children not providing hands on assistance.(5) It should be noted that the median annual income of adult children caregivers is slightly smaller than the median annual income of adult children without caregiving responsibilities – $54,720 and $55,000, respectively.

Many adult children could become informal caregivers

At any point in time, most adult children do not have long-term care responsibilities. Nearly one-quarter – 23 percent – of adults age 51 or older have living parents but do not provide any assistance. For the most part, this is because their parents don’t need any assistance. About 87 percent of adult children that are not providing care report that none of their living parents need help with basic everyday activities.(6)

Adults without living parents could become caregivers

About two-thirds – 66 percent – of adults age 51 or older do not have any living parents, but they may have other family members, such as a spouse, sibling, or a friend, with long-term care needs. In 1999, 41 percent of informal caregivers were caring for a spouse, 10 percent were caring for other relatives, and 5 percent were caring for a non-relative.(7)

Adult children caregivers are similar to adult children that do not provide care

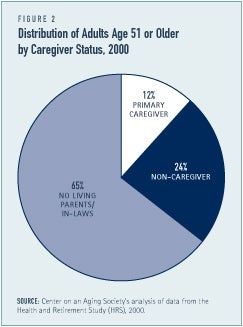

Differences between adult children caregivers and adult children who have living parents but do not provide care are generally quite small (See Figure 3). The populations vary the most with respect to gender. Over half – 53 percent – of primary caregivers are adult daughters, compared to 43 percent of non-caregivers. Caregivers are somewhat less likely to be married than non-caregivers. Roughly three-quarters – 76 percent – of informal caregivers are married compared to 79 percent of non-caregivers. Unmarried, adult daughters, living with the care recipient are most commonly the child that assumes the role of primary caregiver to a parent that needs assistance performing basic everyday activities.(8)

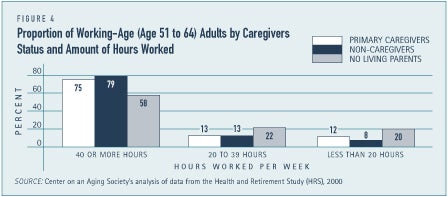

Adult children have work responsibilities

The majority of both adult children caregivers and non-caregivers are employed, and they devote significant amounts of time to their work. Similar proportions of caregivers and non-caregivers of working-age (age 51 to 64) are employed — 63 percent and 65 percent, respectively. Three-quarters of employed caregivers of working-age work full time — 40 or more hours per week (see Figure 4). A slightly larger proportion – 79 percent — of adult children that do not have caregiving responsibilities work full time. Adults without living parents are less likely to be employed, and if they are employed they are less likely to work full-time. More than one-quarter — 28 percent — of adults without living parents were working for pay and 58 percent of employed adults without living parents were employed full time.

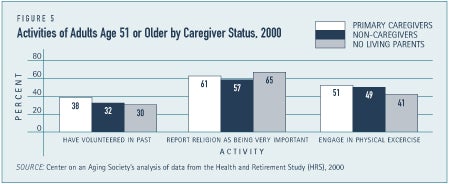

Adult children engage in activities other than caregiving

In addition to providing help to a parent, caregivers seem to find the time to also help out in their communities as well as participate in leisure activities (See Figure 5). Almost two out of five caregivers — 38 percent — volunteer at a hospital, school, church or other organization in their community. In comparison, 30 percent of adult children not providing care to a parent engage in some form of volunteer work. Religion is also very important to caregivers as is physical exercise. Half of caregivers engage in vigorous exercise on a regular basis and almost two-thirds — 61 percent — report religion as being very important.

Conclusion

Family caregivers are a critical component of the long-term care system. Long-term care is primarily provided by family members and friends. Adult children, most of whom have other responsibilities, represent the largest proportion of primary caregivers of older persons, devoting significant amounts of time and resources providing care. As an increasing proportion of the population gets older, more people will likely need assistance with basic activities of daily living. Competing demands, from work and family, are likely to make it harder for families, in particular adult children, to respond to the pressures associated with their parents needs.

1. Mack, K. and Thompson, L. (2004) A Decade of Informal Caregiving: Are today’s informal caregivers different than informal caregivers a decade ago? Data Profile (Washington, DC: Center on an Aging Society), http://www.aging-society.org.

2. Calculations based on data from the Population Division (June 14, 2004) “Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population by Sex, and Five-Year Age Groups for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2003” (Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census), http://www.census.gov/ popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2003-as.html; and Population Projections Branch, Population Division (January 13, 2000) “Annual Projections of the Resident Population by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin: Middle Series (Detailed Tables)” (Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census), http://www.census.gov/population/ www/projections/natdet-D1A.html.

4. Center on an Aging Society’s analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), 2000

7. Center on an Aging Society’s analysis of data from the Informal Caregiver Supplement (ICS) to the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS).

8. Marks, N. F. & Lambert, J. D. (1997) Family Caregiving: Contemporary Trends and Issues Working Paper #78 (Madison, WI: Child and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison), http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/cde/nsfhwp/nsfh78.pdf.

ABOUT THE DATA

Unless otherwise noted, the data presented in this Profile are from the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS) and its Informal Caregivers SUpplement (ICS). Additionally, data from the 1989 and 1994 NLTCS and the ICS to the 1989 NLTCS, are presented to illustrate how informal caregiving has changed over the past decade. The NLTCS and the ICS are sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and conducted by the Center for Demographic Studies at Duke University. The National Long-Term Care Surveys are nationally-representative, household surveys of the population age 65 or older living in both the community and institutional settings. The Informal Caregiver Supplement to the NLTCS collects data on the experiences of the primary informal caregivers of the disabled population age 65 and older living in the community.

The ICS defines p[rimary caregivers as persons providing the most hours of unpaid assistance with either Activities of Daily Living (ADL) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL).

ABOUT THE PROFILES

This is the first in a set of Data Profiles, Family Caregivers of Older Persons. The series is supported by a grant from AARP and MatherLifeWays. This Profile was written by Katherine Mack and Lee Thompson with assistance from Robert Friedland.

The Center on an Aging Society is a Washington-based nonpartisan policy group located at Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the economic and health security of families and people of all ages.