HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment: Are public policies keeping pace with an evolving epidemic?

Visit profiles to view data profiles and issue briefs from the series Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions as well as data profiles on young retirees and older workers.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States is no longer viewed as a new crisis, as it increasingly becomes a chronic condition. The condition requires long-term and expensive medical management and support services, heavily reliant on prescription drugs. A disease that originally was perceived to affect only gay men (especially gay white men) and injection drug users has been found in all sectors of society and throughout the world. In responding to the domestic HIV epidemic in 2003, the central challenges facing policy-makers are how to provide adequate resources to fight HIV/AIDS and how to adapt public policies and programs as the demographic profile of the HIV epidemic in the U.S. changes.

The first cases of what would become known as HIV and AIDS were reported in the United States more than twenty years ago. A previously unknown and terrifying illness spread rapidly. Following an initial period of inaction and denial, the Ameri-can public and governmental institutions have responded to the threat of HIV. An estimated 850,000 to 950,000 people live with HIV/AIDS in the United States, with approximately 40,000 new infections occurring each year. In FY 2002, the federal government alone spent $14.7 billion on prevention, research, and care services related to HIV/AIDS in the United States and around the world.(1)

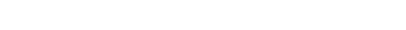

Roughly half of all people living with HIV do not receive regular care

Among people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States who do not receive regular care, about half are unaware of their HIV status (see Figure 1).

Due to advancements in treatment, HIV/AIDS can now be managed as a chronic condition

There is no cure yet for HIV/AIDS, but as people live longer with the condition, they need ongoing care. In addition to basic primary care, case management and care planning services are important because many people living with HIV/AIDS receive services from multiple providers.

Due to a link between HIV and substance abuse, the availability of drug and alcohol treatment and counseling services are important. Many people living with HIV/AIDS have co-occurring mental health problems, including high rates of depression, making mental health services a critical service need. Although definitive statistics are lacking, one study estimates that at least 30 percent of all people with HIV/AIDS require mental health services.(2)

Transportation and other non-medical services play an important role in bringing people into the care system and helping them develop stable and ongoing treatment arrangements. Additionally, steps to mitigate potentially harmful effects from long-term exposure to antiretroviral medications also requires a renewed focus on nutrition, exercise and lifestyle choices, as well as the clinical monitoring of lipodystrophy (fat redistribution) and other complications associated with therapy.

Pharmaceuticals have become the central therapeutic tool in the management of HIV/AIDS

Currently the most important approach to managing HIV/AIDS is highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which suppresses the reproduction of HIV in the body. The goal of antiretroviral therapy is to suppress HIV viral replication so that HIV is undetectable in blood plasma. HAART therapies require combinations of drugs that interrupt different stages of the replication process. Once effective viral suppression is achieved, the goal is to maintain this, while avoiding harmful side effects. Medications to prevent and treat HIV-related opportunistic infections are also critical to the management of the condition. The effective use of pharmaceuticals requires the use of related diagnostic services, such as viral load testing, which is a diagnostic measure of the level of HIV in blood plasma.

While the development of resistance, in which a treatment regimen loses its impact, is influenced by many factors, individuals must strive to carefully ad-here to their course of therapy. Imperfect adherence is believed to be a major contributor leading to drug resistance. Individuals who have taken antiretroviral medications in the past may have more difficulty establishing an effective treatment regimen due to the development of resistance. If resistance develops for one drug, whole classes of drugs may be ineffective for individual patients. Further, resistance in individuals can also lead to the development of drug-resistant strains of HIV that spread in the population.

RYAN WHITE CARE ACT:

TITLES AND PROGRAMS SERVE SPECIFIC PURPOSES

The CARE Act provides services to people living with HIV/AIDS who do not qualify for Medicaid, Medicare, or private health insurance, or who have health insurance that does not cover all of the services they need. The CARE Act funds state and local programs that provide primary medical care and support services, access to drug therapies, health care provider training, and technical assistance for funded programs. Significant local and state control of HIV health care planning and service delivery is conducted under the CARE Act.

Major parts of the Ryan White CARE Act include:

TITLE I * EMERGENCY RELIEF GRANTS TO URBAN AREAS

Title I provides funding to eligible metropolitan areas (EMAs) for primary care and support services that enhance access to and retention in primary care. Each EMA is a metropolitan statistical area established by the U.S. Census Bureau that has a population over 500,000 and has reported more than 2,000 AIDS cases for the most recent five-year period. In 2002, there were 51 EMAs.

TITLE II * STATES

States and territories are funded to improve access to primary care and support services that help people living with HIV/AIDS enter into and remain in primary care. Most of the Title II funds are used to support state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs). All 50 states, the District of Columbia and 8 U.S. territories receive Title II funding.

TITLE III * COMMUNITY-BASED PROGRAMS

Grants are made to public and private nonprofit primary care providers for outpatient early inter- vention services.

TITLE IV * CHILDREN, YOUTH, AND WOMEN WITH HIV/AIDS AND THEIR FAMILIES

Grants are made to public and private nonprofit entities to coordinate comprehensive, culturally appropriate, family-centered services and provide primary care, support services, education about living with HIV, and access to research to these target populations.

OTHER CARE ACT PROGRAMS

The CARE Act also supports other targeted initiatives and programs. These include: Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) — Research Models; HIV/AIDS Dental Reimbursement Program; Community-Based Dental Partnership Program; and the AIDS Education and Training Centers (AETC) — Provider Training.

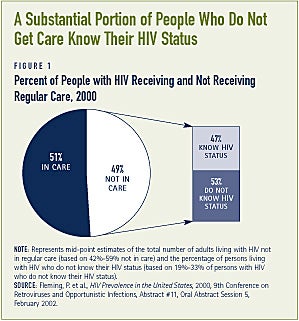

A substantial amount of the care that people with HIV/AIDS receive is publicly financed

Most federal resources for providing HIV care come from three sources: Medicaid and Medicare, which provide health insurance coverage for health and long-term care services and supports, and the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, which funds direct services in communities. The CARE Act fills in gaps left by Medicaid, Medicare, and private coverage by providing health care services to uninsured individuals living with HIV/AIDS and under-insured individuals with HIV/AIDS who have coverage that is insufficient to the meet their health care treatment needs (see Figure 2).

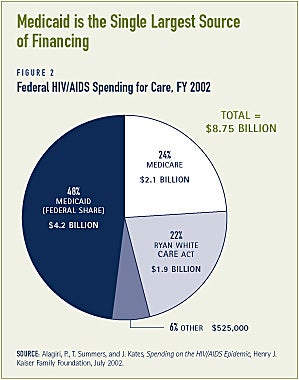

The HIV epidemic in the U. S. largely affects underserved populations

The first cases of HIV/AIDS reported in the United States were among gay men and injection drug users. HIV/AIDS now affects a broader population, but the communities most heavily affected by HIV/ AIDS continue to be groups that are either outside of the mainstream of society or groups that historically have been underserved by the health care system. Three groups in particular continue to be at disproportionate risk for HIV infection: men who have sex with men, which includes gay and bisexual men and those who might not identify as such; people who inject drugs; and racial and ethnic minorities, especially African Americans and Latinos (see Figure 3). Additionally, heterosexuals, largely women, are at increasing risk for HIV infection as are young people. Half of all new cases of HIV infection are believed to occur in young people age 13 to 24.(3)

Changes in current federal programs and policies could improve care for people living with HIV

Government programs play an important role in providing care for people with HIV/AIDS, but the programs have certain limitations.

Some people do not have access to early therapy because of program eligibility rules

The goal of current standards of HIV care is to intervene as early as possible after infection with primary medical care, to carefully monitor disease progression, and to consider initiating anti-retroviral therapy based on certain clinical indicators of disease progression. Ongoing stable access to care is essential. As a consequence of some current program rules, however, health insurance may not be available when it is needed.

MOST CHILDLESS ADULTS WITH HIV ARE INELIGIBLE FOR MEDICAID

Childless adults with HIV generally gain access to Medicaid only by being classified as disabled. They must meet the Social Security Administration’s definition of disability, which specifies that an individual must be unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity, that is, unable to work, in order to be considered disabled. Thus, people with HIV/AIDS generally do not qualify for these programs until they have an AIDS diagnosis. This can present a formidable barrier to early intervention and access to prescription drugs when they are most likely to be effective. Low-income children and some low-income parents with HIV may have an easier time getting Medicaid benefits because they can qualify for coverage without meeting the Social Security Administration’s disability standard.

Policymakers have begun to consider solutions to this problem. Maine, Massa-chusetts, and the District of Columbia, for example, have been granted demonstration waivers by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to extend Medicaid benefits to non-disabled persons with HIV/AIDS.(4) In Maine, participants must be HIV-positive and have an income of less than 300 percent of the federal poverty level.(5) Despite the availability of this flexibility to extend coverage, interested states have had difficulty demonstrating that this type of initiative would be budget neutral to the federal government — an administratively imposed requirement for this type of demonstration waiver. A relatively small number of states have taken advantage of these opportunities by exploring the feasibility of expanding Medicaid to people living with HIV who are not yet disabled through a demonstration waiver. Legislation has been proposed in Congress — the Early Treatment for HIV Act (ETHA) — that would create a new state option in Medicaid for offering Medicaid coverage to low-income people with HIV/AIDS who do not have AIDS. If enacted, states would not have to show budget neutrality to extend coverage to people with HIV/AIDS.

CONGRESS HAS RECOGNIZED THE IMPORTANT ROLE OF COMMUNITY INPUT

The majority of federal funds provided through the CARE Act are distributed with extensive community input. Indeed, the CARE Act stresses the role of local planning and decision-making — with broad community involvement — to determine how to best meet HIV/AIDS care needs. A priority focus is on meeting the needs of traditionally underserved populations hardest hit by the epidemic, particularly people living with HIV/AIDS who know their HIV status and are not in care. Because the communities where HIV has had the greatest impact have been poorly served by the mainstream system, cultural competence in delivering health care services is essential.

Congress has also recognized the unmet needs of minority communities. Since 1999, Congress has provided new funding (not simply earmarking existing HIV funding) to support a Minority HIV/AIDS Initiative across six federal agencies. The purpose of these funds is to help build the capacity of community members and community-based institutions to respond to the HIV epidemic. The Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus have played an instrumental role in establishing this initiative and ensuring that it remains a funding priority.

INCOME ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS FOR MEDICAID ARE LOW

In most states, persons who are disabled and eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), qualify for Medicaid. SSI is an income support program operated by the Social Security Administration for low-income people with disabilities. A related program, Social Security Disability Insur-ance (SSDI) provides income support payments to workers who become disabled. Monthly SSDI payments vary based on past contributions. Individuals receiving SSDI qualify for Medicare after a waiting period. Low-income SSDI recipients can receive SSI to supplement SSDI if the level of their SSDI payment is below the SSI income standard. The SSI income standard for an individual is $552/month in 2003, or 74 percent of the federal poverty level.(6) There are individuals, however, who are too sick to work (and maintain private coverage), but who have too much income to qualify for Medicaid coverage. Many individuals with disabilities receiving SSDI have incomes near or below the poverty level, but still have too much income to qualify for Medicaid. In March 2003, the average monthly SSDI benefit for disabled workers was $836, above the poverty level and considerably higher than the SSI income standard.(7) Therefore, the average SSDI beneficiary has too much income to qualify for SSI and related Medicaid coverage. This inadvertently creates a penalty for working.

States have the option of providing full Medicaid benefits to people with disabilities and the elderly with incomes up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level, $748/ month for an individual in 2003.(8) Nine-teen states use this option.(9) States may also choose to disregard a certain amount or type of income, such as SSDI payments, when determining eligibility for Medicaid.(10)

MEDICARE COVERAGE IS AVAILABLE TO PEOPLE UNDER AGE 65 WHO HAVE DISABILITIES, BUT ONLY AFTER A WAITING PERIOD

As with Medicaid, most people living with HIV/AIDS are ineligible for Medicare until they meet the Social Security Administra-tion’s disability standard. Even then, individuals do not immediately qualify for Medicare coverage. There is a 29-month waiting period from the date that individuals first meet the Social Security Adminis-tration’s disability standard. That is, individuals must wait 5 months to receive SSDI and then the Medicare waiting period is 24 months from the first receipt of SSDI. Thus, individuals who qualify for Medicare already have AIDS and may not have had access to early treatment. Eliminating or shortening the waiting period could make Medicare coverage available earlier in the course of the disease.

Limited access to prescription medications is problematic

The on-going effectiveness of antiretro-viral therapy for individuals, and the HIV population at large, depends on stable, uninterrupted access to medications. This is often not possible, however, because of program features.

MEDICAID COVERAGE FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUGS VARIES ACROSS STATES

Medicaid is the most generous public program for providing drug coverage. Under Medicaid, prescription drugs are an optional service that every state provides. There are significant variations in coverage policies from state to state, with some states placing limits on the number of prescriptions that can be filled each month. States can, for example, create formularies or preferred drug lists, they can require prior authorization, they can encourage or require generics, and they can engage in a variety of drug utilization review strategies. States can also limit pharmacy expenditures by negotiating supplemental rebates or discounts from manufacturers or reducing fees paid to pharmacists.

States are under extreme fiscal pres-sure, experiencing their worst fiscal crisis since World War II. Forty-nine states and the District of Columbia will make cuts to their Medicaid programs during the current fiscal year and 32 states will cut Medicaid twice during the year.11 As prescription drugs are one of the fastest growing expenses in their Medicaid programs, states enacting Medicaid reduc-tions or program restrictions are focusing heavily on restricting pharmaceutical cost growth. Thirty-two states enacted pharmaceutical cost controls in fiscal year 2002 and 45 states plan to enact new pharmaceutical cost controls in fiscal year 2003.(12)

Most of the cost control strategies available to states are not, of themselves, insurmountable barriers to access to necessary medications. Nonetheless, the heavy focus on enacting new pharmaceutical restrictions creates a greater potential that needy individuals will not be able to obtain the prescription drugs they need. This situation creates a need for Federal and state policymakers to monitor and respond to barriers to access to prescriptions that may result from state efforts to control prescription drug spending. Additionally, some people have advocated that price reductions must be part of the response to pharmaceutical cost growth in Medicaid. Under Federal law, pharmaceutical manufacturers that participate in the Medicaid program must agree to provide rebates. The extent to which this system provides for a fair price for Medicaid purchasers has been the subject of significant controversy. In light of sustained increases in pharmaceutical costs and in recognition of the severe fiscal pressure facing states, a number of stakeholders have advocated for Congress to increase the level of the drug rebate in Medicaid.

MEDICARE DOES NOT COVER OUTPATIENT PRESCRIPTION DRUGS

The lack of a prescription drug benefit is problematic for all Medicare beneficiaries. A national discussion has been taking place over the establishment of a Medi-care prescription drug benefit. In the past, Congress has enacted Medicare policies that differentially benefit the elderly over non-elderly disabled beneficiaries (such as guaranteed issue of Medigap supplementary insurance that is not available to non-elderly Medicare beneficiaries). As the policy discussion takes place over the establishment of a Medicare prescription drug benefit, one important consideration will be that all Medicare beneficiaries gain access to the most comprehensive coverage that is possible. Further, limitations placed on the benefit must take into account the high cost of certain drug regimens (such as HAART therapy) and the high cost of individual drugs.

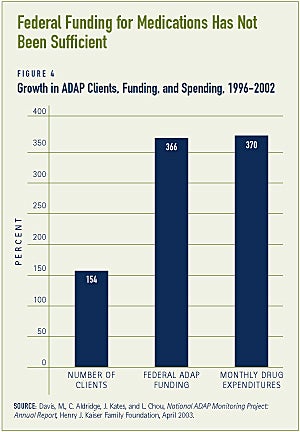

FUNDING FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUGS THROUGH THE CARE ACT’S AIDS DRUG ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (ADAP) HAS NOT KEPT PACE WITH INCREASING NEED

From FY 1996 to FY 2002, the number of clients served by ADAPs increased 154 percent and ADAP monthly drug expen-ditures increased 370 percent. Over this same period, ADAP budget growth of 366 percent has not been sufficient to keep up with increases in the number of clients, increases in drug prices, increased utilization and increased complexity of treat-ment regimen (see Figure 4). The gap between need and available resources can be observed by the number of states that are not able to meet the pharmaceutical needs of their residents with HIV/AIDS. In February 2003, sixteen states reported having one or more ADAP program restriction, such as capped enrollment, limited anti-retroviral access, or expenditure caps.(13)

Not only are ADAPs unable to guarantee coverage for anti-retroviral medications for all who need them, they also do not necessarily cover all HIV medications. In particular, only 15 state ADAP programs cover all 14 highly recommended medications used in the treatment of HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections.(14)

Unlike Medicaid which provides Federal support to match state expenditures, state contributions to ADAPs are voluntary. In 2002, some 16 states did not contribute any state resources to their ADAPs. Due to the state fiscal crisis, states are considering reducing (or eliminating altogether) contributions of state funds to their ADAPs. This is leading to tightening of the ADAP eligibility rules and greater limitations on the range of pharmaceuticals covered. At the same time, states are increasing restrictions in their Medicaid pharmacy programs.

More stable funding could improve care

The Medicaid and Medicare programs establish eligibility standards and benefits packages and guarantee that funding will be available to all who are eligible. The CARE Act is a discretionary program. The funding varies not with the level of need, but with the amount of funding provided each year by Congress and supplemented by the states. Consequently, the CARE Act does not guarantee that any individual will receive a single covered service. This can be problematic because the goal of HIV treatment is to develop on-going stable access to health care services. Fluctuations in funding may limit access to services such as prescription drugs, as well as services such as dental care and nutrition services, which are not always viewed as critical health care services and are frequently not covered by other public or private health care programs.

One solution to the challenge of un- stable financing would be to change the financing structure of the CARE Act to an entitlement program. This is unlikely to happen in the current fiscal environment. Nonetheless, policymakers can focus on developing strategies to maximize Medicaid and Medicare coverage.

Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in responding to the HIV epidemic in the United States. Over the past two decades, the national commitment to providing resources for HIV care and treatment has grown. As the HIV epidemic evolves, it will be important to identify the resources needed to support people living with HIV/ AIDS and to ensure that services and supports provided match the needs and preferences of the population of people living with HIV/AIDS.

1. Alagiri, P., T. Summers, and J. Kates, Spending on the HIV/AIDS Epidemic, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, July 2002.

2. Lee, H.K., et al., “HIV-1 in Inpatients,” Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 43, 181-182, 1995.

3. Youth and HIV/AIDS 2000: A New American Agenda, White House Office of National AIDS Policy, September 2000.

4. http://www.cms.gov/medicaid/waivers/waivermap.asp

5. http://www.cms.gov/medicaid/1115/mehivfct.pdf

6. Social Security Administration and Department of Health and Human Services.

7. Monthly Statistical Snapshot, March 2003, Social Security Administration.

8. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-509).

9. Aged, Blind, and Disabled Medicaid Eligibility Survey, National Association of State Medicaid Directors, October 2001. Note: This includes two states that use the poverty-level expansion but have set an income standard above the SSI level, but below the poverty level.

10. See revised ¤ 1902(r)(2) regulations. State Medicaid Director Letter, #01-007, January 10, 2001.

11. Smith, V., K. Gifford, R. Ramesh, and V. Wacchino, Medicaid Spending Growth: A 50-State Update for Fiscal Year 2003, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2003.

13. Davis, M.D., C. Aldridge, J. Kates, and L. Chou, National ADAP Monitoring Project: Annual Report, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2003.

ABOUT THE ISSUE BRIEFS

This is the second in a series of Issue Briefs on Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions. This series is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foun-dation. The Issue Briefs accompany the Center’s ongoing series of Data Profiles in the same series. Jeffrey S. Crowley wrote this Issue Brief.

The Center on an Aging Society is a non-partisan policy group located at Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the financial and health security of families and people of all ages.