Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services: Whose responsibility is it to ensure care?

Visit profiles to view data profiles and issue briefs from the series Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions as well as data profiles on young retirees and older workers.

Approximately one in five — over 14 million — children and adolescents in the U.S. have mental health problems.(1) Mental health disorders are not limited to specific genders, races, or socioeconomic levels. If untreated, they may cause suffering, disability, stigma, exclusion, and poor quality of life. Some mental health disorders last only a short time, while others are potentially lifelong. Mental health disorders are treatable. Many children and adolescents with mental health disorders recover and grow up to lead healthy and productive lives. The chances of optimal recovery are much better with affordable and accessible mental health services, however. Mental health services for children and their families are complicated by multiple pathways to treatment and multiple funding streams for services. Strategies to improve care include increased funding for services, comprehensive insurance coverage of mental health services, and coordinated prevention and treatment approaches.

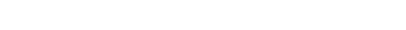

More than three-fourths of children and adolescents do not receive the mental health care they need

Unmet need for mental health care is extremely high for children and adolescents — 79 percent of 6- to 17-year-olds do not receive the services they need.(2) Unmet need is even greater for uninsured children and Latino children — some 87 percent of uninsured children and 88 percent of Latino children do not receive the mental health care they need.(3)

Children and adolescents who do not receive the care they need when they are young are more likely to be dependent on mental health and other social service systems when they are adults.

Youth with mental health disorders are at risk

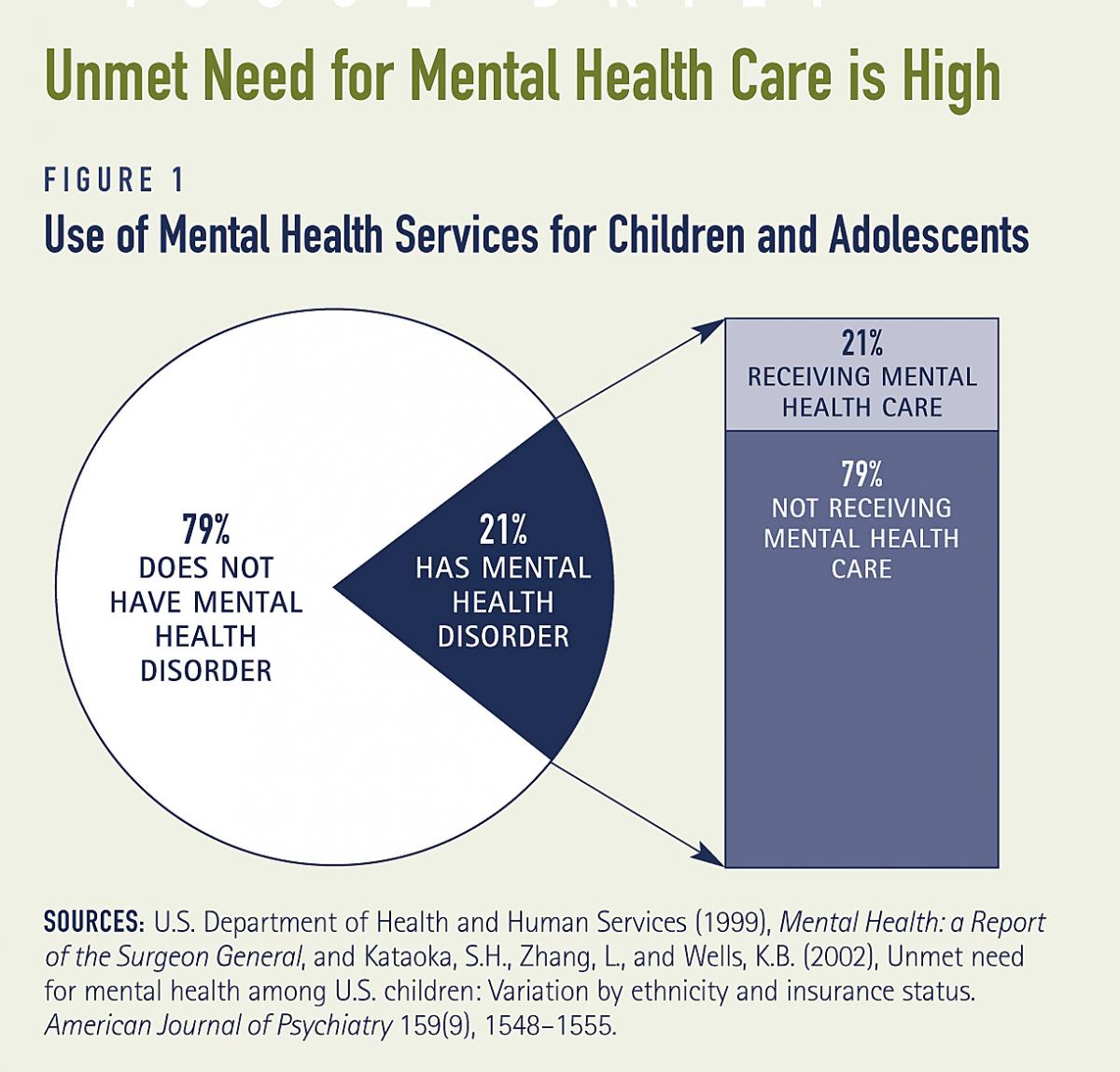

Many children with mental health disorders have poor educational outcomes, and subsequently, poor economic outcomes. Of children and adolescents age 14 and older identified with emotional disturbances, only 42 percent graduate from high school (see Figure 2).(4) Students that drop out of school have difficulty getting and keeping jobs, and therefore have low levels of employment or hold multiple short-term jobs. As a result, these students earn less income than students with other disabilities.(5) The consequences of dropping out of school extend beyond employment for youth with mental health disorders. Within three years of leaving school, 70 percent of these students are likely to be arrested. Children who have been incarcerated continue to have problems throughout their life, including drug abuse and involvement with social services and corrections.(6) Some 74 percent of 21-year-olds with mental health disorders had mental or emotional problems as a child.(7)

Mental health disorders are associated with suicide

More than 90 percent of children and adolescents who commit suicide have a mental health disorder.(9) Yet, estimates from the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse indicate that only 36 percent of children and adolescents at risk for suicide in the previous year received mental health treatment.(10) Suicide is the third leading cause of death for youth age 15 to 24.(11)

Mental health disorders often co-occur with substance abuse disorders

Adolescence is a difficult developmental period. Youth who are experiencing disturbing symptoms of a mental health disorder in addition to the normal developmental issues of adolescence may be at higher risk of substance abuse and dependence.(12) Almost 43 percent of young people who receive mental health services also have a co-occurring substance abuse disorder.(13) Adolescents with serious behavioral problems are seven times more likely to be dependent on alcohol or illicit drugs than adolescents with fewer or less severe behavioral problems.(14)

Children with mental health disorders are overrepresented in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems

Some of the factors that put youth at risk for abuse, neglect, and delinquency include poverty, poor housing and neighborhood conditions, parental substance abuse, and domestic violence. These same conditions increase risk of mental health disorders. As a result, the proportion of children with mental health disorders in these systems is high. Some 50 to 75 percent of children and adolescents placed in foster care have mental health disorders.(15) Rates of emotional disturbance among youth served by the juvenile justice system are between 60 and 75 percent.(16)

WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH?

The United States Surgeon General defines mental health in childhood and adolescence by “the achievement of expected developmental cognitive, social, and emotional milestones and by secure attachments, satisfying social relationships, and effective coping skills. Mentally healthy children and adolescents enjoy a positive quality of life; function well at home, in school, and in their communities; and are free of disabling symptoms of psychopathology.”(8)

The mental health of children and adolescents is best understood as a dynamic process of development within a social context that includes their families, peers, and larger cultural and physical environments. Adolescence in particular is marked by dramatic and constant developmental changes. Some signs and symptoms of mental disorders, such as depressed mood, may also be characteristic of normal adolescent development. Symptoms and behaviors that cause distress and impairment to the child or adolescent, their families, and others in their social environment are indicative of a mental health problem, however.

Insurance coverage does not ensure mental health care

Insurance coverage of mental health care is an important determinant of what type of care and how much care children receive. Mental health care for children and adolescents can be financed through private insurance, out-of-pocket payment, public insurance, or publicly-financed agencies. Some 67 percent of youth are covered by private insurance plans and some 25 percent are covered by public insurance plans. Although the majority of children and adolescents have insurance, mental health coverage varies. Limits on coverage under private health insurance, restrictions on eligibility for public health insurance, and state budget shortfalls have affected access to mental health care for children and adolescents.

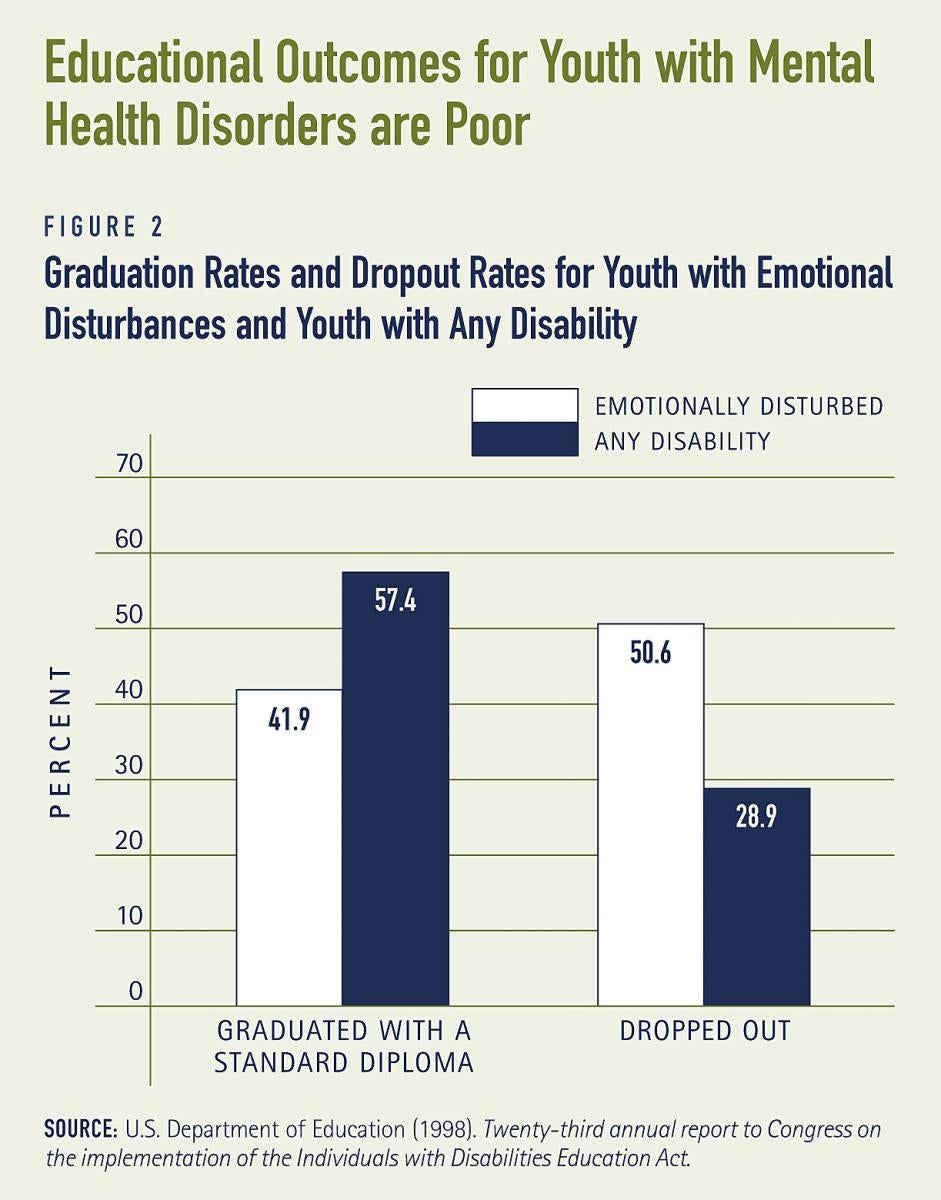

Mental health services under private health insurance coverage are often limited

Private health insurance generally pays for acute medical problems. Mental health services usually include short-term outpatient counseling, medication treatment, and short-term inpatient hospitalization. There may be limits on the number of visits to mental health providers or the types of medications covered. More comprehensive coverage may include intermediate services such as respite care and partial day hospitalizations or day treatment. Among people with private insurance, spending for mental health services has not kept up with total health care spending and has dropped substantially for children and adolescents. For example, combined mental health and substance abuse spending dropped from 13.4 percent of total employer-based private insurance spending in 1992 to 6.6 percent in 1999 for children age 0 to 17 (see Figure 3).(17) This decline may be indicative of a trend by private insurers towards decreasing coverage of behavioral health services in general and increased use of prescription drugs to treat disorders.

Mental health parity refers to efforts to finance mental health care on the same basis as physical health care. The passage of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 prohibited some employer-sponsored group plans from imposing annual or lifetime restrictions on mental health benefits that were lower than those imposed on other benefits. This legislation did not eliminate other limitations on mental health coverage, such as the number of visits that are reimbursable or amounts of co-payments. The Paul Wellstone Mental Health Equitable Treatment Act, introduced in 2003, would require all employers that elect to provide mental health benefits to provide coverage, co-payments, and deductibles that are comparable to medical and surgical coverage.(18)

Medicaid is an essential component of the mental health care safety net

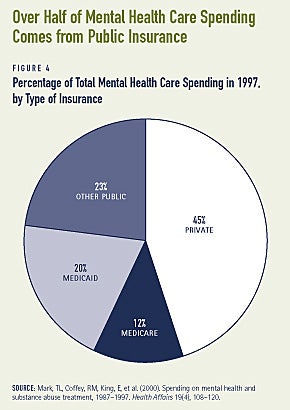

The Medicaid program has become an important insurer of last resort for those with the most severe problems and fewest resources. Some 20 percent of all mental health care spending is paid for by Medicaid (see Figure 4).(19) Medicaid can finance a broad range of outpatient, inpatient and rehabilitative services for youth with mental health disorders, including many psychotropic medications. In addition, Medicaid pays for long-term care for children who need more intensive services, usually through hospitalization or residential treatment. States may also cover optional services such as in-home services, school-based services, and case management through Medicaid. The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program requires states to provide Medicaid-eligible children with all necessary medical services, including mental health services.(20) Despite this mandate, many children served by Medicaid are not receiving comprehensive screenings through EPSDT, reducing access to necessary services.(21) States have also provided health care coverage to some children with family incomes that are too high to qualify for Medicaid through the State Child Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP). All S-CHIP plans cover mental health services, but these are typically inpatient and outpatient services, rather than school-based health services or residential care.

The recent downturn in state fiscal conditions and rising health care costs have led states to make cuts to the Medicaid budget. Some low-income children may lose health care coverage, and those who continue to be insured may face a reduction in various services, including mental health. Budget cuts may decrease the costs to the Medicaid program initially, but may also result in substantial cost-shifting to other systems, such as state and local mental health, special education, child welfare, and juvenile justice agencies.

The uninsured have fewer options

Those who do not have private insurance and are not eligible for Medicaid or S-CHIP have limited options if they need mental health care. More than nine million children were uninsured in 2001.(22) State and local mental health agencies provide some services for uninsured children. The type and amount of services provided differ depending in great part on budgets in states or localities, however.

Managed care may be problematic for those with severe problems

Managed care has become increasingly important in the organization and financing of mental health services. Overall, managed care has tended to ensure greater access to basic behavioral health and community-based services for children and adolescents. Access to inpatient care has been reduced, however.(23) In private plans, managed care has been used to contain costs by limiting inpatient hospital stays, closely monitoring outpatient service use, and developing and expanding intermediate care services as an alternative to more expensive inpatient care. Managed care models can provide a range of cost-effective services to meet the mental health needs of some children and adolescents. Youth with complex, recurring, or long-term mental health problems require more comprehensive services, however, which are often not available through managed care plans.(24)

Managed care has also become a central feature of the Medicaid program for some children. Managed care programs within Medicaid have implemented cost-cutting strategies similar to private managed care models, such as reducing reliance on inpatient care, reducing fees paid to providers, and reducing the number of outpatient treatment sessions.(25) These strategies have not been as effective for children with Medicaid coverage, who tend to have more severe and chronic disorders and need longer-term care.(26)

Home- and community-based care options are scarce

If a child with a mental or physical disorder resides in a hospital or other medical institution for more than 30 days, he or she becomes eligible for Medicaid state plan services, regardless of parents’ income. Medicaid coverage continues only as long as the child resides in the institution, however.(27) Once a child no longer needs institutional care, appropriate home- and community-based services are often necessary to make the transition successful. Provisions for these types of services are not typical in private or public insurance plans. Without adequate aftercare plans and provision of outpatient services the child’s condition may deteriorate, creating a revolving door of hospitalizations and diminishing meaningful progress toward recovery.

Federal law provides state Medicaid programs two options to help children with mental or physical disabilities live at home with their families. Neither option has been widely adopted by states for children with mental health disorders. The TEFRA option, also known as the Katie Beckett option named after the child whose situation led to this policy, is used by some 20 states for children with disabilities. In half of these states, none of the children qualified for this option as a result of a mental or emotional disorder, however.(28) States also have the option of applying for home- and community-based services (HCBS) waivers, which allow states to expand services so that children with mental or physical disorders can remain at home, rather than being placed in institutional care. Only three states have opted for a federal waiver to cover home- and community-based services specifically for children with mental or emotional disorders. Other states have HCBS waiver programs that target a broader population, and children with mental health disorders may be receiving services through these programs. Even in states with waiver programs, however, families may encounter waiting lists. Significant barriers, such as limited state funds or the requirement that services be less expensive than institutional placement, have prevented states from seeking HCBS waivers.(29)

Mental health costs are not limited to insurers and consumers

Schools are the most commonly used resource for children and adolescents with mental and emotional disorders. In 2001, some 47 percent of the youth who received mental health treatment sought help from school counselors, school psychologists, or teachers.(31) Federal special education law requires school systems to provide special education services to children and adolescents with disabilities that interfere with their academic progress. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), children with serious emotional or behavioral disorders are entitled to assessment, counseling, behavior management, and special classes or schools. If the necessary mental health services are unavailable, schools are required to use their own funds to send children with serious emotional or behavioral disorders to specialized private day schools or to long-term residential schools, sometimes out-of-state. Despite this mandate, parents and advocates report that children are not receiving the necessary mental health services through the school system.(32)

Mental health services, though not the primary mandate of child welfare and juvenile justice agencies, are a crucial part of providing a safe or rehabilitative environment for youth in these systems. Child welfare and juvenile justice funds often must be used to create or purchase needed mental health services that are not available through Medicaid or state mental health agencies. The child welfare and juvenile justice systems also help support the mental health needs of youth in group home care, therapeutic foster care, and residential treatment.

Preventive services are essential

Activities that promote healthy development and prevent mental disorders early in childhood improve outcomes for children throughout their lives. Prevention programs have the potential to address problems early before they become unmanageable or the behavior becomes destructive. For example, Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) is a comprehensive program aimed at developing social and emotional competencies, reducing aggressive and acting-out behavior, and enhancing the educational process for elementary school children. Use of the PATHS curriculum has shown an increase in children’s ability to understand social problems, recognize emotions, maintain self-control, tolerate frustration, and develop effective conflict resolution skills.(33)

Resources can be used effectively through comprehensive and coordinated approaches

The mental health system for children and adolescents has multiple entry points, which may increase access, but also may create problems. Often, one agency provides services without knowledge of other agencies that are involved. This type of fragmented care duplicates services, wastes valuable resources, and can be ineffective or even harmful to the youth. The lack of coordination among agencies and funding streams can be frustrating for parents, providers, and advocates.

Recognition of this problem prompted federal officials, in partnership with a growing family movement, to create programs to integrate service delivery systems across mental health, education, child welfare, and juvenile justice. One of the largest ongoing programs is the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, created in 1992.(34) The philosophy of this “systems-of-care” approach is to provide comprehensive, child and family-centered, culturally relevant services. After two years of services, severe behavioral and emotional symptoms decreased in 42 percent of the children in this program.(35) Overall, case management has been identified as one of the strongest components of the system of care. Case managers link families with services, ensure good communication among providers, and help families identify resources.(36)

As part of a plan to sustain the program, grant communities were encouraged to expand funding by developing ways to match federal grant dollars that slowly decline over the 5-year funding period. Many grant communities were able to sustain their programs by combining or blending funding from the mental health, juvenile justice, and child welfare systems to provide needed services.(37) This type of coordination uses resources more effectively and increases the ability of service providers to coordinate care for youth who need services from multiple systems of care.

THE BURDEN FOR FAMILIES IS MORE THAN FINANCIAL

The family must bear a direct financial burden for treatment when insurance does not sufficiently cover mental health disorders or when insurance is unavailable. Some parents who qualify for Medicaid must carefully monitor their financial situation, sometimes by declining promotions or raises, to stay within income limits for the Medicaid program. Families also endure tremendous emotional and physical burden. Not only must they provide physical and emotional support to their children, but also must deal with the stigma associated with these disorders. Family members may experience a range of feelings and consequences, including their own emotional reactions to the illness, the stress of coping with the symptoms and behaviors, and the disruption to their household and work routines.(30) Managing appointments, attending meetings, and advocating for their children are all activities that may be time-consuming and result in social and economic losses for parents.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author.

2. Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., &Wells, K. B. 2002. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry 159(9), 1548-1555.

4. U.S. Department of Education. 1998. Twenty-third annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: Author.

7. U.S. Public Health Service. 2000. Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author.

9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2002. Substance use and the risk of suicide among youths. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, The NHSDA Report. Retrieved March 24, 2003, from http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/2k2/ suicide/suicide.htm.

11. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Suicide Prevention Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 20, 2003, from http://www.cdc.gov/ ncipc/factsheets/suifacts.htm.

12. Friedland, R. Substance Abuse: Facing the Costs. 2002. Washington, DC: Center on an Aging Society, Georgetown University.

13. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2002. Report to Congress on the Prevention and Treatment of Co-Occurring Substance Abuse Disorders and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved May 12, 2003, from http://www.samhsa.gov/reports/ congress2002/chap1ucod.htm#3.

14. National Council on Disability. September 2002. The well-being of our nation: An inter-generational vision of effective mental health services and supports. Washington, DC: Author

15. Webb, M.B., Harden, B.J. 2003. Beyond child protection: Promoting mental health for children and families in the child welfare system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 11(1), 49-58.

16. National Council on Disability. September 2002. The well-being of our nation: An inter-generational vision of effective mental health services and supports. Washington, DC: Author.

17. Mark, T.L., Coffey, R.M. 2003. What drove private health insurance spending on mental health and substance abuse care, 1992-1999? Health Affairs 22(1), 165-172.

18. See http://www.theorator.com/bills108/s486.html.

19. Mark, T.L., Coffey, R.M., King, E., Harwood, H., McKusick, D., Genuardi, J., Dilonardo, J., Buck, J.A. 2000. Spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1987-1997. Health Affairs 19(4), 108-120.

20. Under EPSDT, children with Medicaid are entitled to periodic screening services and any medically necessary service within the scope of the program even if that service is not included in the state Medicaid plan.

21. U.S. General Accounting Office. 2001. Medicaid: Stronger efforts needed to ensure children’s access to health screening services. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved July 3, 2003 from http:// frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/useftp.cgi?IPaddress=162.140. 64.21&filename=d01749.pdf&directory=/diskb/wais/data/gao.

22. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. 2003. The uninsured and their access to health care. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved March 20, 2003 from http://www.kff.org/content/2003/ 142004/142004.pdf.

23. Stroul, B.A., Pires, S.A., Armstrong, M.I., Meyers, J.C. 1998. The impact of managed care on mental health services for children and their families. The Future of Children 8(2), 119-133.

25. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author.

27. Koyanagi, C. 2002. Avoiding cruel choices: A guide for policymakers and family organizations on Medicaid’s role in preventing custody relinquishment. Washington, DC: Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. Retrieved March 3, 2003, from http://www. bazelon.org/issues/children/publications/TEFRA/index.htm.

30. World Health Organization. 2001. Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2002. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-17, DHHS Publication No. SMA02-3758. Retrieved February 25, 2003, from http://www. DrugAbuseStatistics.SAMHSA.gov.

32. National Council on Disability. September 2002. The well-being of our nation: An inter-generational vision of effective mental health services and supports. Washington, DC: Author.

33. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA Model Programs: Effective Substance Abuse and Mental Health Programs for Every Community. Rockville, MD: Author. Retrieved April 15, 2003, from http://modelprograms.samhsa. gov/textonly_cf.cfm?page=model&pkProgramID=24§ion= description.

34. SAMHSA’s National Mental Health Information Center. 2003. Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children Program. Rockville, MD: Child, Adolescent, and Family Branch, Division of Service and Systems Improvement, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved March 31, 2003, from http://www.mental health.org/publications/allpubs/ CA-0013/default.asp.

35. Center for Mental Health Services. 1999. Annual report to Congress on the Evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, 1999. Atlanta, GA: ORC Macro.

ABOUT THE ISSUE BRIEFS

This is the third in a series of Issue Briefs on Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions. This series is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Issue Briefs accompany the Center’s ongoing series of Data Profiles in the same series. Emily Ihara wrote this Issue Brief with assistance from Laura Summer.

The Center on an Aging Society is a non-partisan policy group located at Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the financial and health security of families and people of all ages.