Workers Affected by Chronic Conditions: How can workplace policies and programs help?

Visit profiles to view data profiles and issue briefs from the series Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions as well as data profiles on young retirees and older workers.

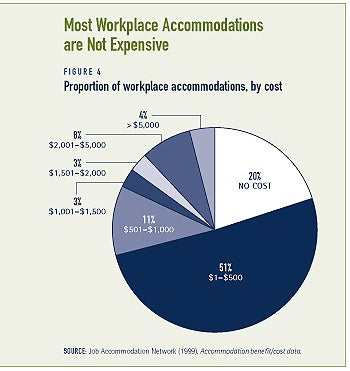

Workers are affected by chronic conditions in two critical ways – by their own conditions and by the need to care for family members with chronic conditions. Although some individuals are disabled by chronic conditions, better health technology and disease management programs, as well as flexible work policies, are helping many people affected by chronic conditions function in the workplace. Changes in the workplace need not be expensive – more than half of workplace accommodations cost less than $500, and 20 percent cost nothing.(1) Workplace policies and programs that address the needs of workers affected by chronic conditions are beneficial to workers and employers alike. Workers who are able to balance their work and family responsibilities through use of flexible work policies have higher job satisfaction. Employers, in turn, are able to achieve cost savings through increased productivity and employee retention.

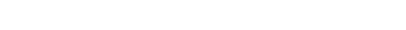

More than one-third of adults age 18 to 65 have at least one chronic condition

Some 58 million adults – 34 percent – age 18 to 65 have at least one chronic condition, and 19 million adults – 11 percent – have two or more chronic conditions (see Figure 1).(2) The growth in the number of older workers will increase as the baby boom generation ages.(3) The number of workers with chronic conditions is also likely to increase. It is estimated that by the year 2020, half of the U.S. population will have at least one chronic condition and one-quarter will be living with multiple chronic conditions.(4)

More than one-third of workers are caregivers for family members with chronic conditions

Labor market productivity is affected when people must leave the workforce, reduce their hours, or take a temporary leave of absence to care for family members who are chronically ill. Some 35 percent of workers report that they have provided care for a family member 65 years of age or older in the past year.(5) Family members who need care may be any age, although older adults are more likely to be affected with chronic conditions. Regardless of the age of the person who needs care, caregivers’ concerns and needs in the workplace may be similar.

Chronic conditions are costly for workers and businesses

Beyond the health care costs of treating chronic conditions, workers and employers incur indirect costs from reduced productivity and lost work days. A national study conducted in 2001 found that 37 percent of workers with heart disease, 20 percent of workers with asthma, and 18 percent of workers with mood disorders missed one or more work days annually due to their condition. Individuals with one of five chronic conditions – hypertension, mood disorders, diabetes, heart disease, and asthma – lose an estimated $36 billion yearly in wages.(6)

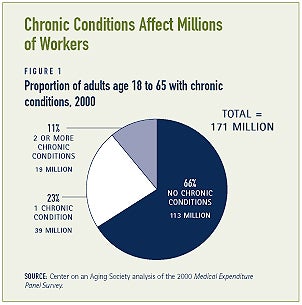

Individuals with chronic conditions are not the only ones affected; caregivers of those with chronic conditions also lose earnings and retirement benefits. In an in-depth study of 55 caregivers who had made some type of work adjustment as the result of their caregiving responsibilities, the financial and productivity losses were high. For example, the average lifetime financial loss for these caregivers was more than $659,000 due to lost wages, social security benefits, and retirement contributions.(7) Caregiving also limits worker productivity and opportunities for job advancement (see Figure 2).

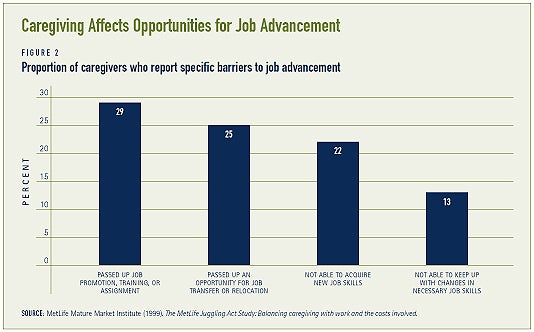

U.S. businesses lose on average more than $11 billion annually due to lost productivity, absenteeism, and turnover of full-time employees who are caring for family members with moderate to intense needs (see Figure 3). When caregivers who are not full-time employees or who are caring for family members with less intense needs are also considered, this estimate increases to over $29 billion.(8)

Employers are recognizing the importance of work-life policies

Employers have been compelled to pay greater attention to their work-life policies and practices due in part to shifting workforce demographics, growing competition for workers, and the increasing globalization of business. Employees with supportive workplaces and better quality jobs have greater job satisfaction and greater loyalty and commitment to the organization’s success.(9) For example, the SAS Institute, a company that develops business analytic software, credits its low employee turnover rate (less than 4 percent, compared to the industry average of 15 to 20 percent) to its wide array of work-life initiatives and the employee-focused philosophy of the company.(10) At the SAS Institute headquarters, there are two on-site childcare centers, an eldercare information and referral program, an employee health care center, wellness programs, and many other work-life programs. SAS employees work in an environment that encourages integration of the company’s business goals with the personal needs of the employees.(11) Larger companies (defined as those with 1,000 or more employees) are more likely than their smaller counterparts to provide flexible work options, elder care programs, employee assistance programs, work-life seminars, health care and wellness programs, and work-life training for supervisors.(12)

WHAT ARE WORK-LIFE PROGRAMS?

Work-life programs strive to create a flexible and supportive work-place environment that helps employees balance their personal and professional lives. Examples of work-life programs include felxible work options, dependent care services, financial assistance, time-off policies, and caregiving and eldercare programs. Work-family initiatives were developed by a small number of companies in the late 1970s and early 1980s to address the needs of the growing number of working mothers in the workforce. More recently, companies have expanded the definition of work-family to work-life in order to address the needs of all workers.

ACCOMODATIONS IN THE WORKPLACE

The needs of workers with some chronic and disabling conditions can be met through the redesigning of jobs and workplaces or modifications to the work environment that remove job-related barriers. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires reasonable accommodations in the workplace to ensure equal access in the application and selection processes, to enable an employee with a disability to perform their job functions, and to enable an employee with a disability to enjoy the same benefits and privileges of employment as other employees.

The Job Accommodation Network, sponsored by the Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy, is a free consulting service designed to increase the employability of individuals with disabilities. Services provided by the Job Accommodation Network include individualized consultation about workplace accommodations, technical assistance regarding the ADA, and other information about funding, education, and services.(13)

Examples of physical accommodations include installation of elevators or lifting aids, increased lighting, more frequent work breaks, and an accepting management climate. Other accommodations include flexible scheduling, job restructuring, job sharing, providing training to staff or supervisors, or changing work procedures. Some employers are concerned that the cost of job accommodation is high, but most workers with disabilities require no special accommodations and the cost for those who do is minimal or much lower than many employers believe. The Job Accommodation Network estimates that the cost of accommodations is typically very low, approximately $250 per employee with a disability (see Figure 4).(14)

Bank of America has established an accommodation program to meet the employment needs of people with disabilities. This program allows employees to request comprehensive disability case management, which includes accommodations consultation, identification, and implementation, from an accommodations specialist. Accommodation Case Managers are on staff at the bank, and work to ensure that the company meets its obligations under the ADA and other state disability laws. They are available to work with an individual from the beginning of the accommodation process to the end.15

ACCOMMODATIONS FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISABILITIES

The costs associated with accommodations for people with psychiatric disabilities may be indirect and ongoing. Such accommodations cannot simply be purchased on a one-time basis. A study of individuals with psychiatric disabilities in supported employment programs described the following accomodations:

- 37% were involved with a job coach (general support, training assistance, or supervision)

- 23% had job coach assistance in hiring (job development, job coach interview assistance)

- 21% had flexible scheduling

- 8% had changes in training and supervision (extra or modified supervision, extended training on the job)

- 6% had modified job duties

- 5% had miscellaneous accomodations (accommodations unrelated to psychiatric disability, transportation assistance, modified work environment, tolerance and behaviors).(16)

FLEXIBLE WORK ARRANGEMENTS

Employees who have flexible work arrangements are healthier, more satisfied with their jobs, and experience better balance between work and family. Flexibility allows workers to have autonomy and control in achieving their work goals.(17) This type of work arrangement is especially helpful for individuals with chronic and disabling conditions and working caregivers because workers are able to balance their work and personal needs.

All of the 2003 Best Companies for Working Mothers allow flexible work arrangements, compared to 55 percent of companies nationwide.(18) Employers and workers are increasingly viewing flexibility in the workplace positively. For example, 70 percent of managers and 87 percent of workers report that flexible work arrangements have a positive or very positive impact on productivity.

The type of employer or job may have some influence on whether workers will benefit from such policies. For example, shift workers or low-wage workers may not be given the opportunity to access these kinds of benefits.

FLEXIBLE WORK ARRANGEMENTS: WHAT ARE THEY?(19)

FLEXTIME: Employees vary the duration and timing of the workday within limits set by management. Traditional flextime is a schedule with a fixed start and end time. Daily flextime allows employees to vary their work hours on a daily basis.

PART TIME: Working less than full time hours.

COMPRESSED WORK WEEKS: Working full time hours in a reduced number of days such as 4/40, where over a one-week period, employees work 10 hours for 4 days.

TELECOMMUTING: Working away from the office some or all of the time.

JOB SHARING: Two workers cover one full time job.

PAID AND UNPAID LEAVES: To care for dependents, education, or ther reasons.

SABBATICALS: Paid or unpaid time off at recurring intervals.

LEAVE POLICIES

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993 requires that companies with 50 employees or more within a 75-mile radius of one of their worksites must provide 12 weeks of unpaid, job-guaranteed leave for childbirth, adoption, foster care placement, a serious personal medical condition, or care of a child or spouse with a serious medical condition to employees who have worked at least 1,250 hours over the preceding year.

Unfortunately, many working Americans – some 78 percent of workers – are unable to take advantage of this law because they cannot afford to take unpaid leave.(20) States are trying various models in an attempt to help families maintain financial security while balancing their family responsibilities.

For example, in the state of Washington, the “Sick Leave for Sick Families” bill was signed into law in 2002. The bill allows workers – public and private – to use sick leave and other paid leave to care for a child with a medical condition requiring treatment or supervision, or to care for a spouse, parent, parent-in-law, or grandparent who has a serious health condition or an emergency condition. Other states, such as Arizona and Hawaii, have also proposed this type of initiative.(21)

In other states, such as California, New Jersey, and New York, lawmakers have introduced plans to extend temporary disability insurance benefits to workers who take family and medical leave. California signed SB 1661 into law in 2002, expanding the state’s disability insurance program to provide up to six weeks of wage replacement benefits to workers who take time off to care for a seriously ill child, spouse, parent, domestic partner, or to bond with a new child.(22)

Another model – under consideration in Illinois – creates a cost-sharing fund, with contributions from the employer, employee, and state, and provides employees on leave with partial wage replacement. In Hawaii, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Washington, states have proposed establishing temporary disability Family Leave Insurance funds, financed by small payroll contributions by employers and/or employees, which would help working families.(23)

RESOURCE AND REFERRAL SERVICES

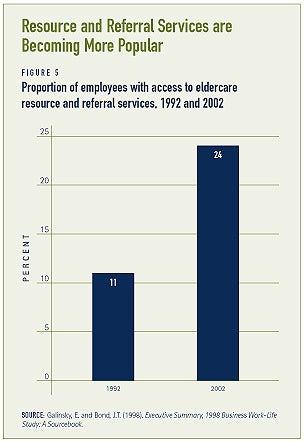

Resource and referral services are becoming increasingly popular. In companies with 100 employees or more, the proportion of employees with access to eldercare resource and referral services more than doubled between 1992 and 2002 (see Figure 5).(24)

Companies can provide a range of work-life information and support services to inform workers of the range of resources that are available to them. For example, the MetLife Mature Market Institute provides research, training and education, consultation, and information about aging, long-term care, retirement, and the 50+ marketplace for MetLife employees and MetLife’s business partners. Examples of seminars and workshops provided include “Working Care-givers: What Managers Need to Know,” “Working in the Mature Market,” and “You and Your Aging Parents.”(25)

Other companies have developed actual services in addition to resource and referral services. In 2001, Merrill Lynch developed a national Family Care Association for all of its U.S. employees. These associations provide services such as back-up care for sick and well children, back-up care for adults, child and adult care vouchers, and a resource and referral service.(26)

SUPPORT FOR WORKERS

Workers who are dealing with their own chronic conditions or those of their family members may experience increased stress. Eldercare support is meant to help working caregivers with their struggle to balance their jobs with their commitments to care for elderly parents or ill spouses, or to care for elderly parents at the same time they have dependent children still at home.

Supportive supervisors and work-places can make a difference for workers’ morale and dedication. Although individual management styles may differ, companies can make an effort to encourage and develop supportive supervisors through training programs. In a survey of for-profit and not-for-profit companies with 100 employees or more, only 43 percent of companies trained super-visors to respond to the work-family needs of their employees.(27)

Employee Assistance Programs are also good potential sources of support. These programs differ for each organization, but the overall goal is to address productivity issues by helping employees identify and resolve personal concerns. Employee Assistance Programs are increasingly seen as a way to keep workers productive and healthy by avoiding problems in the first place. Some 56 percent of companies with 100 employees or more provide Employee Assistance Programs that address work-life issues. Other strategies to reach a broader audience include seminars or workshops. Some 25 percent of companies provide seminars or workshops on issues such as care of the elderly or work- family problems.(28)

EMPLOYER POLICIES AND INTERVENTIONS FOR WORKERS

Employer policies have direct effects on work experiences and environments. They also have immediate and long-term effects on workers, their families, and their communities through direct and indirect mechanisms.

DIRECT MECHANISMS include interventions on specific worker behaviors, conduct, and exposures; delivering general health promotional programs to individual workers; and providing and structuring health and disability insurance programs.

INDIRECT MECHANISMS include sufficient work income that can provide resources for improving one’s general environmental health and safety. Monetary resources can be used to purchase needed health services, both preventive and theraputic. Work sites may also provide social contacts and networks that create additional opportunities for workers to receive information relevant to maintaining healthy lifestyles and avoiding health threates.

Health promotion may be enhanced through the employee benefit structure. For example, respite care or felxible leave policies that allow workers to attend to ailing parents, in the process, help decrease worker stress and maintain worker health status.

Other possible health promotion programs include:

- Education in providing caregiving skills

- Nutritional and dietary interventions for older workers

- Polypharmacy and therapy management programs

- Tailored exercise interventions

- Disease screening

Conclusion

Workplace policies and programs have the potential to play an important role in the lives of workers who are affected by chronic conditions. Options are available to policy makers and employers to address workers’ needs. Such efforts have already made an impact on some workers’ ability to balance their work and family life. Continued attention to these issues will help improve the quality of life for workers and increase workplace productivity.

1. Job Accommodation Network (1999). Accommodation benefit/cost data. Retrieved May 24, 2004, from http://www.jan.wvu.edu/media/STATS/BenCosts0799.html

2. Center on an Aging Society analysis of data from the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

3. Rix, S.E. (2004). Aging and work – A view from the United States. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

4. Anderson, G. (2002). Chronic conditions: The cost and prevalence of chronic conditions are increasing. A response is overdue. Expert Voices (Issue 4). Washington, DC: NIHCM Foundation. Also, Partnership for Solutions (n.d.) Chronic conditions: The problem. Retrieved April 27, 2004, from http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/problem/index.cfm

5. Bond, J.T., Thompson, C., Galinsky, E., Prottas, D. (2002). Executive Summary, Highlights of The National Study of the Changing Workforce. New York: Families and Work Institute.

6. Druss, B.G., Marcus, S.C., Olfson, M., Taniclian, T., Elinson, L., & Pincus, H.A. (2001). Comparing the national economic burden of five chronic conditions. Health Affairs, 20, 233-241.

7. MetLife Mature Market Institute (1999). The MetLife Juggling Act Study: Balancing caregiving with work and the costs involved. New York: Author.

8. MetLife Mature Market Institute (1997). The MetLife Study of Employer Costs for Working Caregivers. New York: Author.

9. Galinsky, E. & Bond, J.T. (1998). Executive Summary, 1998 Business Work-Life Study: A Sourcebook. New York: Families and Work Institute.

10. Business for Social Responsibility (2001). Issue Brief: Work-Life. Philadelphia, PA: Author. Retrieved April 26, 2004, from http://www.bsr.org/CSRRResources/IssueBriefDetail.cfm

11. The SAS Institute (n.d.). Work/Life. Retrieved May 10, 2004, from http://www.sas.com/corporate/worklife/index.html

13. The Job Accommodation Network website available at http://www.jan.wvu.edu/

14. VCU-RRTC on Workplace Supports (2002). Tapping new talent for business success: Employing people with disabilities. Richmond, VA: Author.

15. VCU-RRTC on Workplace Supports (2002).

16. MacDonald-Wilson, K.L., Rogers, E.S., Massaro, J. M., Lyass, A., Crean, T. (2002). An investigation of reasonable workplace accommodations for people with psychiatric disabilities: Quantitative findings from a multi-site study. Community Mental Health Journal, 38: 35-50.

17. Casey, J.C. & Chase, P. (2004). Creating a culture of flexibility: What it is, why it matters, how to make it work. Boston College: Center for Work & Family. Also, Business for Social Responsibility (2001).

18. Working Mother (2003). 100 Best in Class: 2003. Retrieved May 10, 2004, from http://www.workingmother.com/oct03/100BestInClass

20. AFL-CIO (n.d.). Family and medical leave. Retrieved March 9, 2004, from http://www.aflcio.org/issuespolitics/worknfamily/

21. National Partnership for Women and Families (n.d.). Paid leave gains momentum at state and federal level. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved March 9, 2004 from http://www.nationalpartnership.org/

22. National Partnership for Women and Families website available at http://www.nationalpartnership.org/

23. National Partnership for Women and Families (n.d.).

25. MetLife Mature Market Institute website available at http://www.metlife.com

26. Corporate Voices for Working Families website available at http://www.cvworkingfamilies.org/innovations.html

ABOUT THE ISSUE BRIEFS

This is the seventh in a series of Issue Briefs on Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions. This series is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Emily Ihara wrote this Issue Brief.

The Center on an Aging Society is a non-partisan policy group located at the Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the financial and health security of families and people of all ages.